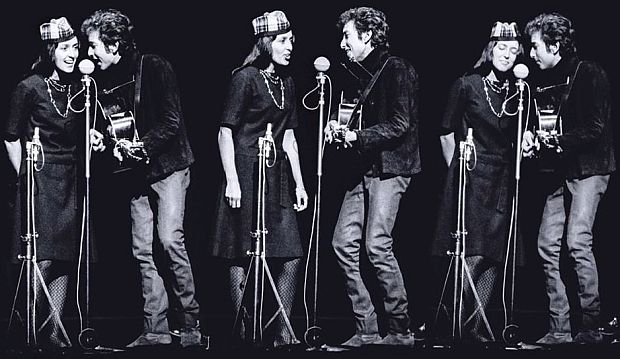

Joan Baez joins Bob Dylan on stage for a memorable live performance that charts their diverging paths.

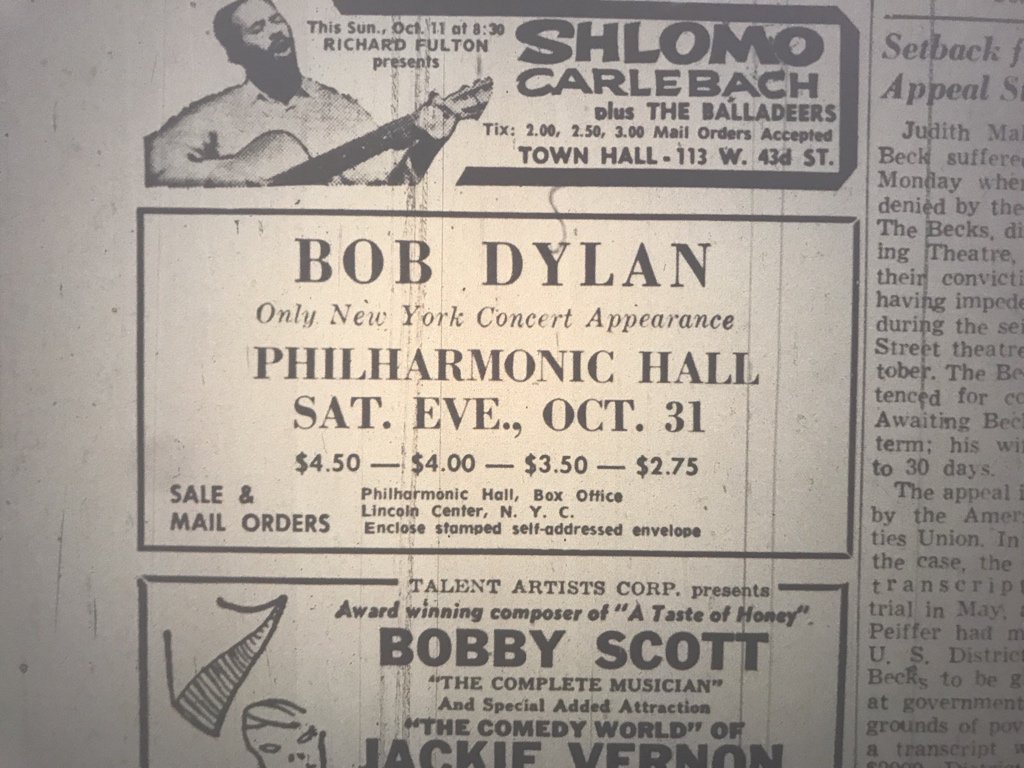

Whenever I watch Bob Dylan documentaries like Dont Look Back, Rolling Thunder Revue and No Direction Home, Joan Baez is always one of my favourite characters. The same happens when I listen to The Bootleg Series Vol. 6: Live 1964 – Concert at Philharmonic Hall.

Joan Baez only features on four of the 19 songs Bob Dylan performed at New York’s Philharmonic Hall on Halloween 1964. But – like any time I see her talk about Dylan or perform with him – her energy, humor and good nature shine through during this brief appearance.

From the moment she takes the stage, Baez is jocular and playful. Duetting with Dylan on Mama You Been On My Mind, she breathily sings “chooga chooga chooga” behind his train-like guitar.

Yet she’s also being played with. Dylan stretches his intros to each verse on Mama and she struggles to follow him. At first, making their duets difficult seems like Dylan having fun, but it may also be tinged with a streak of malice.

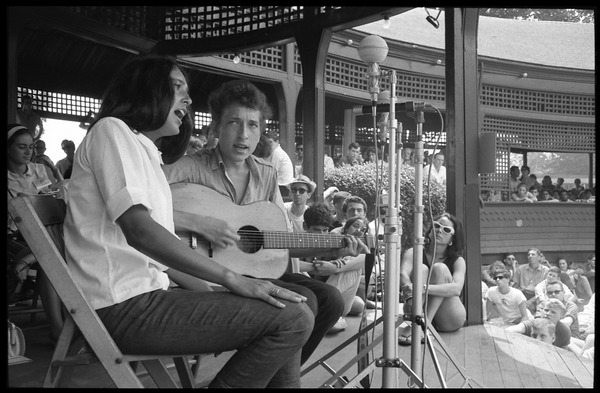

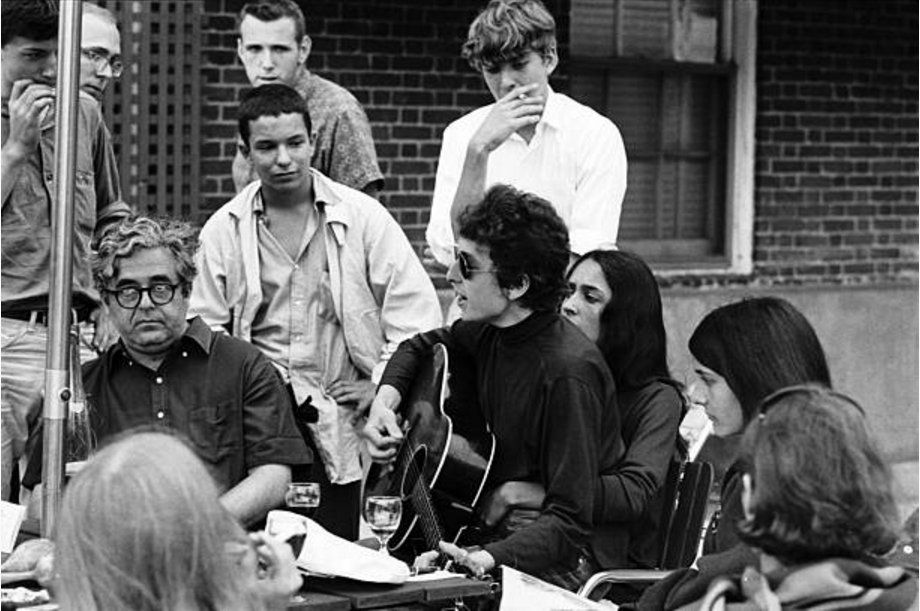

Dylan had grown tired of sharing his spotlight with Baez. A spotlight that was once hers. One of the biggest breaks of Dylan’s career came when Baez invited him on stage with her at Newport Folk Festival in 1963.

Four years earlier Baez had made her own name in folk circles with a Newport appearance, having also been handed an opportunity through a guest slot.

After her father got a job at MIT and moved the family from New York to Massachusetts, Baez briefly attended Boston University. However, her focus was less on her studies and more on singing at the city’s folk clubs, as well as nearby Cambridge’s famous Club 47. Through these performances, she met key figures in the folk revival including Eric Von Schmidt, Odetta and her eventual Newport champion, Bob Gibson.

The latter had been working as a salesman in New York City when in 1953 he helped a new friend to build a house. That lucky homeowner was Pete Seeger who inspired Gibson to quit his job, buy a banjo and become a folk musician. A couple of years later, he had a year-long residency at Gate of Horn, the Chicago folk club run by Dylan’s future manager Al Grossman.

After getting to know Baez when he visited Cambridge, he helped her get bookings at Grossman’s club then invited her to join him at Newport. Though he had been instructed by the festival organisers not to bring anyone else on stage with him, the generous Gibson gave over half his short set to showcasing the 18-year-old Baez’s angelic voice on a pair of religious songs.

First was Virgin Mary Had One Son, with Gibson playing a 12-string guitar and providing sweet harmonies while Baez pierced the quiet with her extraordinary quiver. Then the pair sang Crossing River Jordan, a boisterous gospel song co-written by Gibson with Tom Geraci, that must have a similar spiritual source to Ray Charles’ I Got a Woman. Gibson had more of a lead on this one, but Baez’s powerful harmonies are impossible to escape.

She later recalled how “an exorbitant amount of fuss was made over me when we descended from the stage” and the singer soon had Columbia and Vanguard Records chasing her signature. Unlike Dylan, she chose the latter, believing that she’d had more creative freedom away from a major label.

Gibson would later downplay his role in Baez’s ascension to the role of folk music’s “barefoot Madonna”, describing it as “like ‘discovering’ the Grand Canyon. Someone was bound to notice it was there!” Baez may have felt the same when four years later at Newport, she was singing With God On Our Side and introducing her adoring audience to the song’s fresh-faced writer.

While Dylan’s career likely would have continued on its upwards trajectory without Baez’s Newport intervention, she certainly helped it gain pace. So much so that, just 12 months on, the tables had turned. Dylan was not just a star of the folk scene, he had become an icon. Now when they sing With God on our Side at the Philharmonic Hall, he’s the headliner, changing lyrics so she can’t sing along.

Like the Philharmonic Hall audience, Joan Baez laughs off Dylan’s performative jabs. She seems generous, open-hearted and very much in love in ways that Dylan decidedly wasn’t. Baez was also still extremely committed to the protest scene and almost had to drag the hesitant Dylan onstage to perform at the March on Washington in August 1963.

A year later at The Philharmonic Hall, he’s increasingly indifferent to the protest persona that his appearance alongside Dr. King helped cultivate. Dylan’s reluctance is expressed in the way he rushes into the set’s opening song, The Times They Are a-Changin’. The anthem that used to kickstart his live show now sounds like a chore to get out of the way.

He follows up Times with a great performance of Spanish Harlem Incident, a song whose symbolist sway is emblematic of Bob Dylan’s Another Side. Dylan returns to topical themes with Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues, whose introduction the audience applauds.

The set continues this one-for-them, one-for-me approach with a harmonica-heavy To Ramona followed by the boxing death interrogation, Who Killed Davy Moore?

The audience may have thought Dylan was sticking with topical themes when they heard the next song’s opening, “Of war and peace…” But it’s a bait’n’switch. This is the first time most will have experienced the intense surrealism of Gates of Eden, which he had debuted at Boston’s Symphony Hall a week earlier.

The Philharmonic crowd’s respectful, but likely baffled, applause at the conclusion of Gates of Eden contrasts with the bawdy laughter and roars of approval that greet another new song, If You Gotta Go, Go Now (Or Else You Got To Stay All Night).

The audience laps up Dylan’s upbeat performance of this fun song packed with witty one-liners, whose studio outtake was only released on Bootleg Vol. 2 in the early 90s, though Manfred Mann would had a UK hit with their 1965 cover.

Dylan offers his audience some more topical crowd pleasers, ending the show’s first half with the rapturously received A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall. He opens the second half with Talkin’ World War III Blues then plays a fine version of The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, just before Joan Baez joins him onstage.

As she waited in the wings, Dylan’s protest partner may have grown frustrated as he unleashed more new songs that strayed from the topical template. Of course, Bob Dylan was not really done with political music, he was simply reinventing it. He first played It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) on Sep 1st, 1964 at Philadelphia’s Town Hall. Two months later he’s enthralling New York’s Philharmonic audience with a thrilling performance (mistakes and all) of this extraordinary nine-minute epic.

I imagine Joan Baez would have appreciated It’s Alright Ma’s scything social critique even as she urged Dylan to refocus on more specific causes and concerns. Little did she suspect that I Don’t Believe You’s ignored ex-lover would prove all too relevant to her own cause during the following year when she accompanied an increasingly distant Dylan on his UK tour, as documented in Dont Look Back.

How the times had changed. As the relatively unknown Bob Dylan was cutting his debut record in Nov 1961, Joan Baez was selling out New York’s Town Hall. She had also just released her second album, Joan Baez, Vol. 2, which went gold.

At the Philharmonic Hall in 1964, Baez went back to her debut record, called – you guessed it – Joan Baez. Her solo vocal performance of that album’s opener Silver Dagger, with Bob Dylan accompanying on guitar, is wonderful.

Baez followed up her hit sophomore record with a pair of concert albums (you can work out the titles), both of which also sold well. The second live set contained her first Dylan covers, With God On Our Side and Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright. Dylan performed the latter at the Philharmonic and provided a preview of how he’ll adapt his vocals when he needs to be heard over a loud electric backing band. Come on down, shouty Bob.

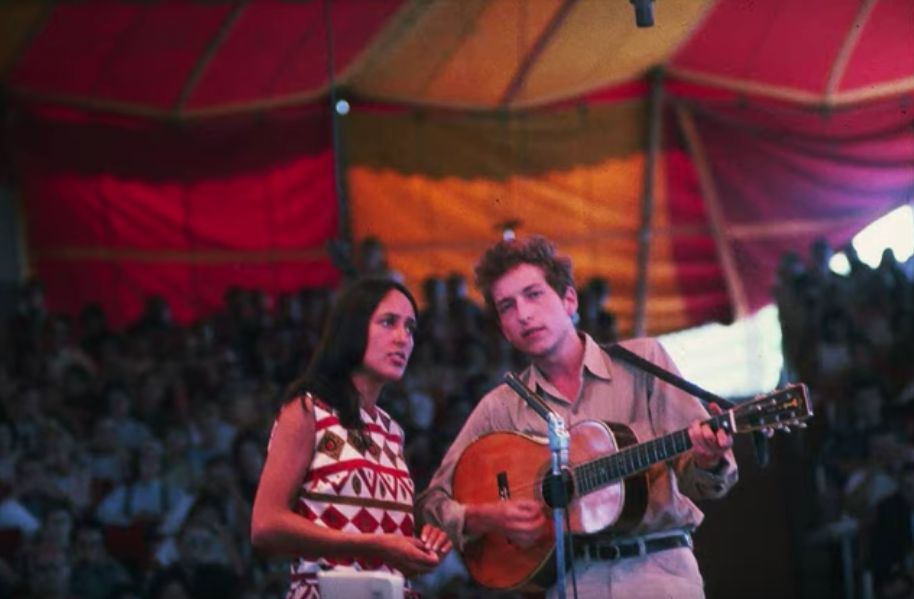

Baez had first sung With God on Our Side with Dylan at the Monterey Folk Festival in California in May 1963 then again at Newport in July. At the following month’s Forest Hills Music Festival, she performed the song solo but then brought Dylan out to duet on five songs in front of nearly 15,000 people packed into the Tennis Stadium in Queens, New York.

With a line-up including Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald and the Dave Brubeck Quartet, the 1963 Forest Hills Music Festival wasn’t as folk-focused as Dylan’s other major appearances that year. And the folk artists on the bill like Baez, Peter Paul and Mary and The Kingston Trio represented the more palatable side of the genre.

The Forest Hills audience may have found Dylan’s staccato delivery of Only a Pawn in their Game to be more abrasive than the weekend’s other entertainment and certainly a stark contrast with Baez’s musical beauty. The pair also performed duets of Hard Rain, Blowin’ in the Wind and Dink’s Song (though there’s no recording of the latter) at the festival, as well as a one-off Dylan original, Troubled And I Don’t Know Why.

Based on What Did The Deep Sea Say?, a song that Woody Guthrie sang with Cisco Houston, Troubled is a funny, country-tinged song that Dylan might have improvised as he sang. His effective mix of blues and comedy drew laughter and applause from the audience, especially after he mentioned a squalling television that “never said nothing at all”.

Forest Hill ’64 was the only time Dylan performed Troubled And I Don’t Know Why and I don’t believe this unique recording has ever been included on any of his official collections. However, the duet does feature on Baez’s Rare, Live and Classic compilation from 1993, even though she doesn’t do much more than provide backing vocals on the chorus.

As an updated version of an older song complete with contemporaneous relevance, Troubled represents Dylan’s influence on Baez. She had largely been a reverent interpreter of traditional folk songs. As their personal and professional relationship developed, she performed more of his and other songs that increasingly aligned with her interest in the wider social issues of the times.

Dylan, however, was leaving that scene behind, while also using more drugs, which Baez despised. While he always insists that Mr. Tambourine Man isn’t a drug song, its woozy insularity clashed with Baez’s growing outward reach. At the Philharmonic show, he played a fine version of that song, right before Hard Rain, creating another contrast with that older song’s clear-eyed external observations.

A few months before, Dylan had performed Mr. Tambourine Man at the 1964 Newport Festival. This time he and Baez appeared together as equals; the king and queen of the folk crowd. Dylan joined Baez’s set for It Ain’t Me Babe and she sang With God on Our Side during his closing night set.

They’d duet on both these songs when he again appeared as her guest at the Queens Tennis Stadium for the 1964 Forest Hill Festival. The other song performed at that event on August 8th was Mama You’ve Been On My Mind, which he had first played for Baez during a Newport afterparty at the Viking Motor Inn.

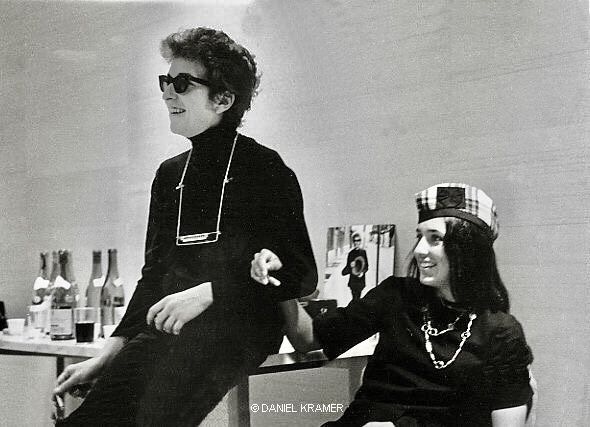

In a candid photograph from those informal motel sessions, Baez is clinging to Dylan, who is seated on her lap. At first glance, they seem like a close-knit couple, though with the hindsight of where their relationship was headed, it’s hard not to note that he his back to her.

At the Philharmonic Hall, Dylan began their duet section by messing her around on Mama You Been On My Mind. By their combined conclusion of It Ain’t Me Babe, it feels like he’s making a point. Just as the song’s position as Another Side’s closer seemed designed as a farewell to the folk scene, so here Dylan is letting Baez know that he’s not the one for her and her causes.

After she leaves the stage, he’s got one more message for her. Though All I Really Wanna Do was a hit for Cher, this slight song is still an understated way to conclude such a memorable show. Unless “be friends with you” is aimed more at his stage-side lover than the audience in front of him.

Friends is what they will remain and Joan Baez will play further scene-stealing supporting roles throughout Bob Dylan’s career. But the Philharmonic Hall show is where we get the first hints that it was time for her to break with his outsized influence and refocus on her own musical and political path.

What did you think of The Bootleg Series Vol. 6: Live 1964 – Concert at Philharmonic Hall? Did I spend too much time on Queen Joan? Which great Dylan performances did I neglect?

Leave a comment