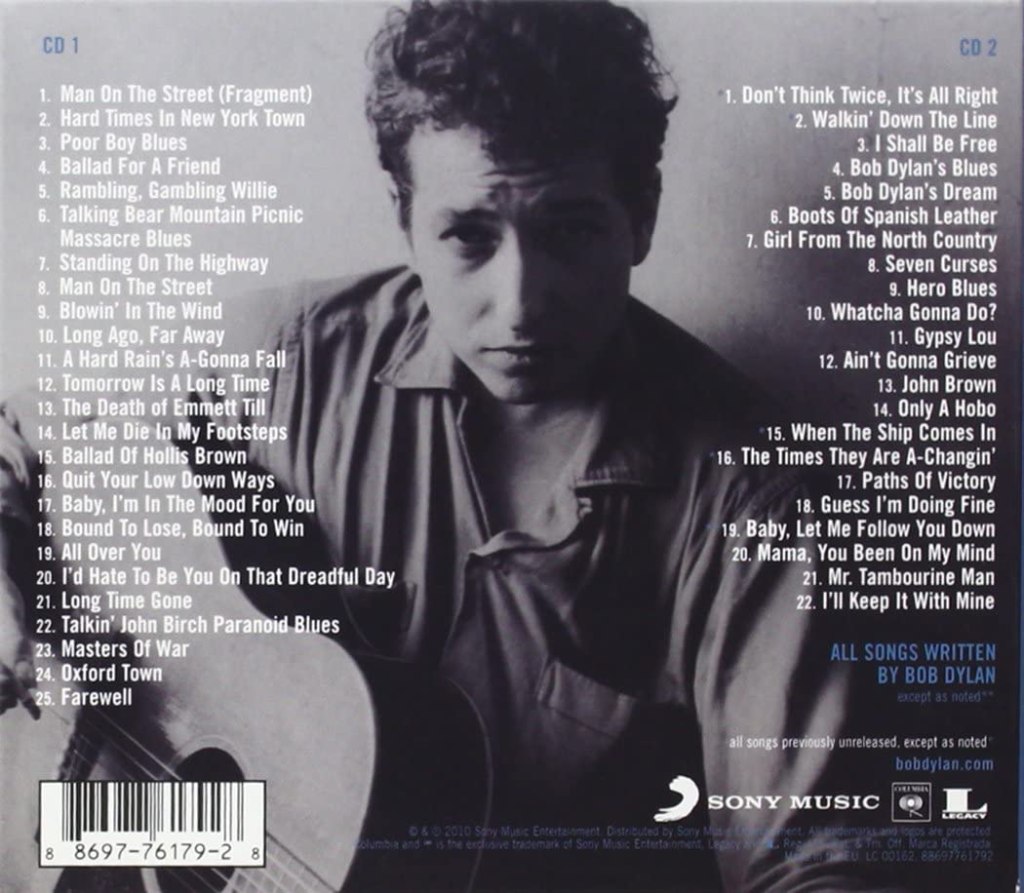

Released in 2010, this collection of demos unearths more songs from those astonishingly productive first years of Bob Dylan’s songwriting career.

In my revisits to Bob Dylan’s first four studio records, early live sets and the first Bootleg volume, I’ve covered 55 original compositions, all written between 1961-64. But The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos: 1962-64 unearths 15 new songs from that time.

When I revisited Bootleg Vol. 1, I was impressed by the quality of the album outtakes and songs he only ever performed live. Bob Dylan’s cast offs are often superior to the best material of other artists. Does the same apply to his demos?

While Poor Boy Blues shares its name with a Bo Weavil Jackson song from 1926, it is a Dylan original. Granted, the lyrics are largely a collection of standard blues tropes, but then so was Howlin’ Wolf’s sensational 1957 take on the title and theme. Dylan’s jaunty guitar playing is quite different from his usual style around this time, while his tight bluesy vocal is excellent.

Ballad for a Friend is a poignant song about the death of an old pal. It’s set in the North Country so has a sense of being autobiographical and Dylan’s line “a diesel truck was heading down / carrying up a heavy load / left him on a Utah road” captures the tragic ordinariness of road accidents.

Standing on the Highway is a fine fast-paced blues number that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Bob Dylan’s debut album. It’s also a semi-detached precursor to Freewheelin’s more personal, Down the Highway, though the lines “One road’s goin’ to the bright lights / The other’s goin’ down to my grave” do add a touch of melodrama.

These three songs along with Rambling, Gambling Willie and Talkin’ Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues were recorded in one session for Leeds Music Publishing. Dylan also gave them the rights to Man on the Street – cut for, but not included on his debut album – and Hard Times in New York Town. Different versions of these last four songs had already been included on Vol. 1 of The Bootleg Series.

Some Dylan biographers suggest that the $500 (or $1000 – it’s a disputed amount) he received from the Leeds deal helped to spur on Dylan’s songwriting. For a man who spent a lot of time couch surfing, finally earning some decent money must have been a thrill and a serious incentive to keep creating new material.

Leeds didn’t make any money from the seven songs Dylan gave them. At least not until the songwriter’s new manager stepped in to buy out Dylan’s contract. Albert Grossman was keen to sign his man to another publisher, the Witmark of this compilation’s title.

After Bob Dylan fired Grossman in 1971, the Witmark deal emerged a major bone of contention. Dylan alleged that his manager had a secret stake in any money Witmark earned from his artists. Not only was Grossman splitting the contracted royalties with his songwriter, he was also earning a share of the publishing house’s income.

These allegations only came to light in 1981 after Grossman sued Dylan for not paying him the full amounts contractually owed to him. Dylan countersued and later claimed Grossman settled out of court. Others say that Dylan had to pay $2m to his former manager.

The first demo Dylan recorded for Witmark was a beautifully simple rendition of Blowin’ in the Wind. It’s no surprise Grossman rushed through the switch from Leeds by paying back the full value of the original deal. He knew he had a money-spinner on his hands.

Another likely financial winner was Tomorrow is a Long Time, a stunning love song with a keen sense of longing. Featuring a similar delicate finger-picked guitar to Don’t Think Twice, Dylan creates a graceful fusion of bluesy pathos and bucolic folk imagery with an anguished, but somehow still composed, vocal. For some reason, he decided against recording it during The Freewheelin’ sessions, later citing unhappiness with the sentiments of the final verse, though I struggle to hear what the issue may have been.

Instead, the song was picked up by other artists. Perhaps the most well-regarded is the gorgeous version by Judy Collins. Tomorrow is a Long Time has similarities with Seven Curses, which Dylan recorded for Witmark a year later and whose story draws on Collins’ song Anathea.

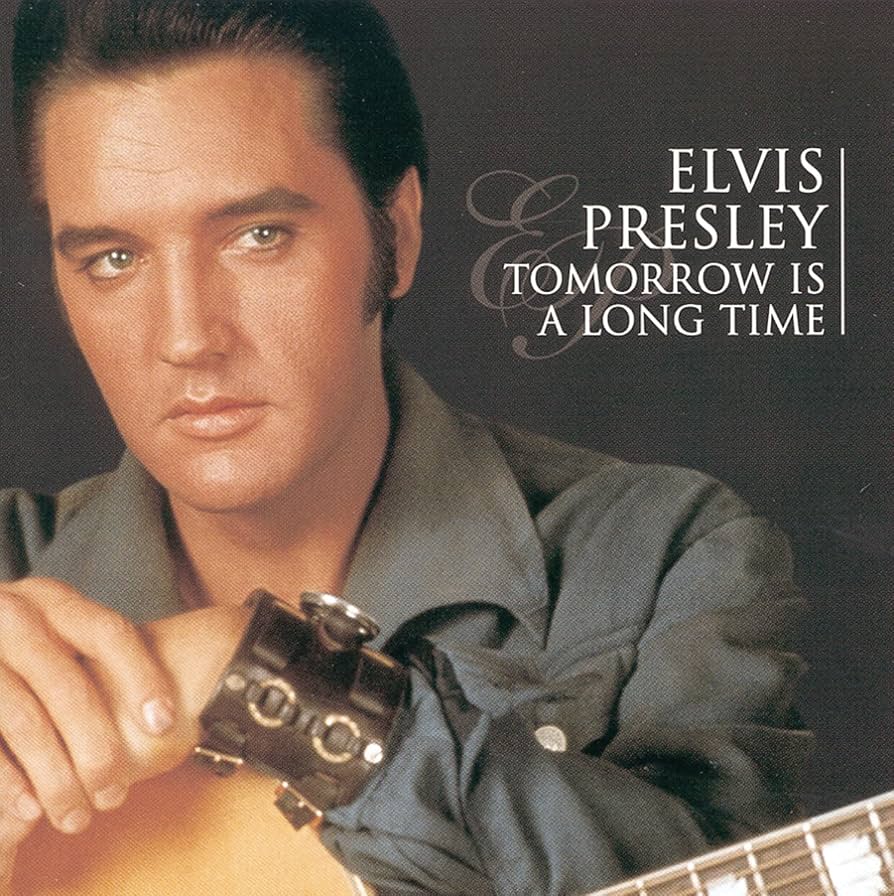

Tomorrow is a Long Time was also recorded by Rod Steward, Odetta (another Al Grossman artist) and Elvis Presley. The latter was introduced to the song by Charlie McCoy, who worked on the King’s gospel album, How Great Thou Art. Having recorded Blonde on Blonde with Dylan in March 1966, McCoy became part of Elvis’ Nashville studio team two months later.

During these sessions, he played Odetta’s version of Tomorrow is a Long Time for Presley, who loved the song and cut his own take even though it didn’t fit with his record’s intended gospel theme. Instead, the song was included on the soundtrack album for Elvis’ 1966 film, Spinout, despite not featuring in the movie.

Clocking in at more than five minutes, Tomorrow is a Long Time was one of the longest songs Elvis had recorded up to that point. With a loose languid rhythm set by DJ Fontana’s tambourine and a sorrowful steel guitar that is presumably played by the King’s regular guitarist Scotty Moore (though future Dylan collaborator and pedal steel specialist Pete Drake also featured on How Great Thou Art), Presley takes his time to explore each mellifluous possibility of Dylan’s words.

The songwriter would later describe Elvis’ cover of Tomorrow is a Long Time as “the one recording I treasure the most”.

In demoing Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues, Dylan plays around with some of the lyrics. He adlibs that the only people he can trust include “me…and Al Grossman”. Perhaps Dylan should have been more paranoid when it came to his manager. Yet, according to Peter Yarrow (of Peter Paul and Mary – another Grossman act): “Personally, artistically and in a business sense, Albert Grossman was the sole reason Bob Dylan made it.”

Peter Paul & Mary’s version of Blowin’ in the Wind helped make Bob Dylan a protest icon (and a lot of money – though much more for Grossman). Part of Dylan’s journey to that status included some topical songs that never made it far beyond the Witmark archive.

The Death of Emmett Till is such a significant song in Bob Dylan’s early catalogue, it’s astonishing to realize that most fans wouldn’t have heard him sing it. Aside from the Folksingers Choice radio show performance, where host Cynthia Gooding described the song as “one of the greatest contemporary ballads I’ve ever heard”, and bootlegged live renditions like the Finjan Club show, the only official recording seems to be the Witmark demo.

Backed by a melody similar to his/Van Ronk’s House of the Rising Sun, Emmett Till is one of the first Dylan songs to deal with racism in America as he recounts the brutal murder of the titular black teenager and castigates Jim Crow and the KKK. Like how Till’s mother insisted on an open casket so the world could “see what they did to my baby”, Dylan’s song details the boy’s torture even if some of it was “too evil to repeat”.

What he’s — rightly — not interested in is what Till was supposed to have done to earn the ire of the two men who kidnapped and killed him. Dylan’s neatly rejects the relevance of any justification with a single dismissive line: “They said they had a reason, but I can’t remember what.” A similar construction is used to underscore how easily the murderers got away with their crime: “And so this trial was a mockery, but nobody seemed to mind.”

The song would soon cease to be part of Dylan’s repertoire, possibly because the Emmett Till story happened in the mid-50s and he wanted his songs to be more topical. While another demo Long Ago, Far Away looks back to historical injustices like slavery, lynching and the crucifixion of Jesus, the point is the sarcastic suggestion of the refrain that such things no longer happen, “DO THEY?” It’s like a proto With God on our Side.

The Witmark Demos also allows us to hear early versions of some of his other protest classics like Masters of War and The Ballad of Hollis Brown, whose title was wisely updated from this version’s The Rise and Fall of Hollis Brown. I think the demo of Oxford Town is even better than the version that made The Freewheelin’. Dylan’s voice is great and the guitar sounds really rich for a demo recording.

Dylan’s vindictive side comes to the fore on I’d Hate to Be You on That Dreadful Day. Rather than the social sneering of songs to come like Positively 4th Street, this has a smug, righteous tone of religious conviction that he’ll return to in the late 70s. Though on this demo Dylan undercuts the judgemental, end-of-days vibe at the end by cheerily calling the song his “calypso tap number”.

Speaking of the apocalypse, while many of the Witmark demos are hurried, run-throughs just to get the melody and words down on tape, Dylan performs A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall with the intensity it deserves.

The demo versions of The Times They Are a-Changin’ and When the Ship Comes In previously appeared on Bootleg Vol. 1. They’re both worth revisiting as Dylan plays them on piano and while Times is a bit loose, Ship is fantastic.

And in a neat reversal, the piano that we heard on the Bootleg Vol. 1 version of Paths of Victory becomes a guitar on the Witmark demo. This version is not as jaunty and subsequently feels less triumphant.

The album The Times They Are a-Changin’ typecast Dylan as a protest singer. And these demos show that he certainly mined this seam in 1963. But he also remained interested in other topics and song styles.

25 of the 47 tracks on The Witmark Demos were recorded in 1963. Songs were flowing out of Dylan and we get to hear the demo versions of classics like Don’t Think Twice, Boots of Spanish Leather and Girl from the North Country.

An amusing example of his productivity is All Over You. Dave Van Ronk said that some guy challenged Dylan, the “hotshot songwriter” to write a song called I Had To Do It All Over Again, I’d Do It All Over You” as the refrain. 24 hours later, Dylan played him this song and won $20 then presumably some royalties after Van Ronk recorded it for his 1963 album, In the Tradition.

Long Time Gone and Gypsy Lou are both blues-inflected, rambling songs, that mention a variety of American place names. The young Dylan was still portraying himself as the weary road warrior, especially on Long Time Gone that repeats the myths he was telling about himself like “ramblin’ around with the carnival trains” and exulting the kind of hard travellin’ he promised Woody Guthrie he wouldn’t claim.

Gospel influences feature on both Whatcha Gonna Do? and the truncated Ain’t Gonna Grieve. The former was also recorded during the Freewheelin’ sessions but that outtake hasn’t been officially released. It shares some day-of-judgement vibes with I’d Hate To Be You, but is much less self-satisfied.

Hero Blues is another lost song from The Freewheelin’, which Dylan also attempted while recording The Times They Are a-Changin’ He obviously liked this comical song as he briefly resurrected it during his 1974 tour with The Band, opening his first headline show in five years by hinting to the expectant crowd that he’s not the hero they need.

Other demo versions of songs also recorded during The Freewheelin’ sessions include the fun Baby I’m in the Mood For You – which first appeared on the 1985 Biograph compilation – the gravely blues of Quit Your Low Down Ways and the uplifting Walking Down the Line, song that both previously appeared on Bootleg Vol. 1. Plus, we get demo versions of songs that did make it onto The Freewheelin’: a ragged Bob Dylan’s Blues and a nice performance of Bob Dylan’s Dream.

While the lyrics to Guess I’m Doing Fine are very blues, the music and guitar playing are a bit more country than we’ve heard from Dylan so far. Recorded in 1964, it’s a long way from the more complex stories he’d begun telling on Another Side of Bob Dylan.

Mr. Tambourine Man was originally attempted during Another Side’s sloshed and rushed recording session. On The Witmark Demos, we get a piano accompaniment that is a little plodding and a vocal whose weariness isn’t all that amazing.

Dylan’s voice also sounds tired on Mama You Been On My Mind, another song that he left off Another Side… But here his croak works for this lovely lovelorn piece.

The Witmark Demos concludes with I’ll Keep it with Mine – a song previously heard on Bootleg Vol. 2 as a Blonde on Blonde outtake. The sound quality on this 1964 demo is poor. Dylan would wait a couple of years before attempting to record it properly.

A strength of The Witmark Demos is that you often get insights into how Dylan feels about songs. Whether that’s sitting on them like I’ll Keep it with Mine or how he sometimes loses interest.

The high quality of the outtakes and rarities collected on Bootleg Vol. 1 makes it accessible for even casual Dylan listeners. Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos covers a similar period and many of the same songs, but is more suited to the obsessed.

The obvious issue is that these are demos, so Dylan is naturally more casual about how he performs the songs. The demo of Only a Hobo is nice but lacks the compassion and sorrow he gave it when recording the song during the Times album sessions.

One of the highlights of Bootleg Vol. 1 is Let Me Die in my Footsteps. When recording the same song for Witmark, Dylan cuts it short and asks if they really want it. “It’s an awful drag – I’ve just sung it so many times”.

Dylan interrupts another song — Bound to Lose, Bound to Win — because he can’t remember all the verses and promises to write them out later.

He does the same on I Shall Be Free, the talkin’ blues song that appears on The Freewheelin’. “That’s about all I can remember without my notebook.”

But the big difference between Bootleg Vol. 1 and this Vol.9 is the strength of the previously unreleased songs. For me, a prime example of the (understandably) lesser quality of The Witmark Demos is Farewell.

Written in London during the winter 1962, Farewell is a reworking of the British folk standard, The Leaving of Liverpool. Dylan’s version has been recorded by many other artists, including Judy Collins, Tim Buckley, Lonnie Donegan and Liam Clancy.

Unusually for Dylan, he doesn’t add much to this interpretation. Even when his other musical appropriations warranted a settlement with the original artist — see Jean Ritchie and Nottanum Town — Dylan’s words radically altered the new song — see Masters of War.

But Farewell is based on a song about leaving and continues to be a song about leaving without taking any other departures from the original. For all that early Dylan has been accused of plagiarism, he very rarely failed to put his own stamp on the sources of his inspiration.

The Cohen Brothers used Farewell as the song played by their Dylan character at the end of Inside Llewyn Davis. The poor titular folk wannabe never had a chance of making it if he’s even upstaged by mediocre Bob.

Overall, The Bootleg Series Vol. 9 – The Witmark Demos (1962-64) is a fascinating document of a developing songwriter and performer. But aside from Tomorrow is a Long Time, the demo of Oxford Town and some of the very early Leeds songs, there’s not enough to keep me coming back.

What did you think of The Witmark Demos? More broadly accessible than I’ve suggested or definitely one for the hardcore Dylan fans?

Leave a comment