Looking back at the album that launched an icon.

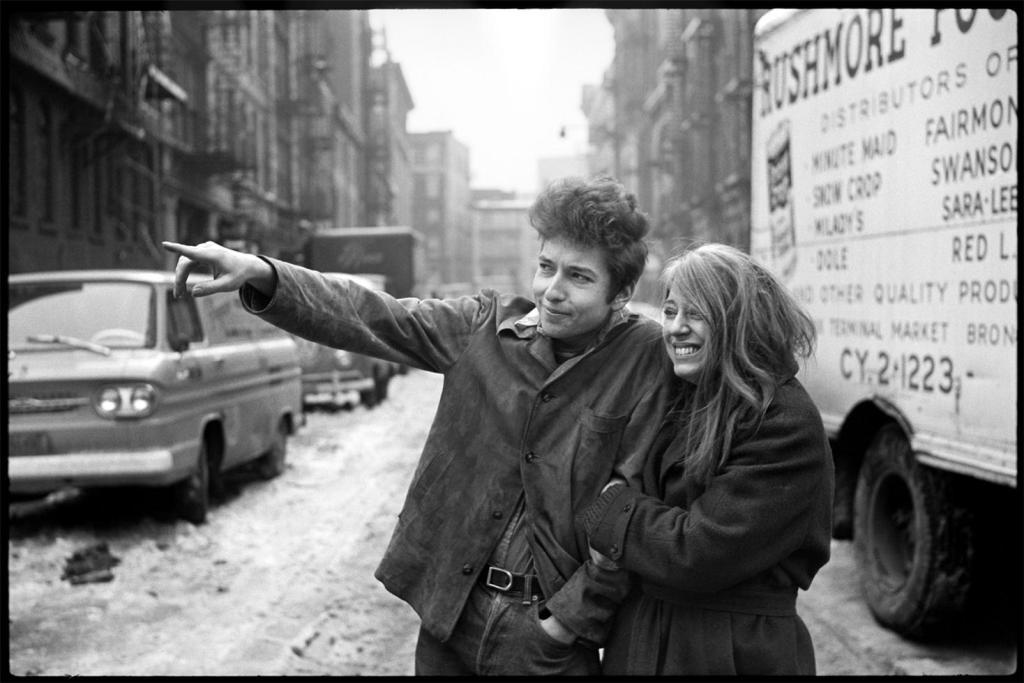

It’s one of the greatest album covers ever. Just look at that image below.

A young couple striding down the middle of the street, braced against the New York cold, bound together by young love. It feels timeless, universal, familiar.

Of course, it’s totally misleading.

The cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan provides an unmistakable impression of unity. But many of the record’s songs are about these lovers being apart from one other and the pain caused by this separation.

As Bob Dylan began recording his second album in April 1962, his girlfriend Suze Rotolo moved to Italy to study. She became his absent muse for the rest of the year, a ghost haunting his songs.

She’s most obviously present on Down the Highway. On an album where Dylan finds his own unique voice, Down the Highway is the one throwback to the blues standards of his debut. It was even recorded in one take, like much of the material on that first record.

But where Down the Highway differs is that this version of the blues is personal, these are very much Bob Dylan’s Blues. He laments how “The ocean took my baby, my baby stole my heart from me. She packed it up in a suitcase and took it away to Italy.”

With an easy and engaging vocal style and excellent guitar playing, Dylan’s rapid evolution is apparent. He’s learned how to take the templates and traditions of old music and make them his own. Use them to express his feelings and concerns.

Sometimes he does that without doing an awful lot with his source material. Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance is credited as a Dylan original but draws heavily for music and lyrics on Henry Thomas’ 1927 song of the same name. What Dylan does add is the force of his personality and an emotional complexity that will become a trademark of sorts.

On Honey Just Allow Me One More Chance, Dylan tosses off vaudevillian humour with lines like “looking around for a girl like you / can’t find nobody so you’ll have to do.” Yet he cannot completely laugh away the desperation that has him “walking down the road with my head in my hands” and the repeated title line is as pleading as it is playful.

The title of Girl from the North Country suggests it’s about one of Dylan’s old flames from Minnesota. An early Dylan classic, his lyrics paint a resonant picture of the frozen land where he grew up, accentuated by his delicate finger-picked guitar and a steady quiet vocal that is filled with wistfulness and longing.

Yet the melancholy is so immediate, Girl from the North Country must also be directed at the absent Suze. That keening harmonica at the end is more than a little heartbroken.

The song’s tune draws heavily on the English traditional, Scarborough Fair. The singer had spent the winter of 1962 in the UK filming a BBC drama, Madhouse on Castle Street. Its director Philip Saville had seen Dylan perform in New York earlier that year and reworked the show’s script to create a role for him.

Dylan acts as a sort of one-man Greek chorus to the action set in a boarding house, singing songs including Cuckoo is a Pretty Bird (a song I discussed in my revisit to The Gaslight Tapes), Hang Me O Hang Me – which Dave Van Ronk had recorded for his Folksinger album that same year – and the Saville-penned Ballad of the Gliding Swan.

The BBC destroyed the only tape of Madhouse on Castle Street in a routine purge of the archive – even though it concludes with one of the first major performances of Blowin’ in the Wind – so evidence of Dylan’s acting debut has been lost. But much more critical for his music career was his meeting with Martin Carthy.

The British folk singer introduced Dylan to many standards from the British and Irish tradition. That included Scarborough Fair, a song that would become a big hit for Simon and Garfunkel, who also learned it from Carthy. Dylan adapted it for Girl from the North Country, again taking the old and spinning something new and masterful from it.

In an album of original material with a strong traditional foundation, Dylan also includes Corrina Corrina, credited as a traditional even though he tweaked the arrangement and lyrics. Of course, some of this is also mined from a rich seam like the lines “I got a bird that whistles, I got a bird that sings” that reference Robert Johnson’s Stones in my Passway.

Corrina Corrina is a lovely song with an appropriately cracked and lovelorn vocal from Dylan. Though perhaps just as interesting is the fact that the recording features a backing band of drums, double bass and beautifully intricate guitar playing, which sounds like it might be by Bruce Langhorne, who will collaborate with Dylan on future albums.

This early electric session also resulted in the non-album single Mixed-up Confusion, which failed to have much of an impact on the charts, and a fun cover of That’s Alright Mama, which sounds like a dry run of Maggie’s Farm.

Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right is another beautiful break-up song, but that closing dismissive line “you just kinda wasted my precious time” is pure bravado. In trying to hide his true feelings, Dylan reveals the extent of his heartache.

The song draws heavily on Paul Clayton’s Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons but as ever Dylan elevates the source material to new heights. Recorded in one take and featuring some of his finest guitar playing, Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right is right up there as one of my favourite Bob Dylan songs.

If the image of enduring love on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan is misleading then perhaps the album’s title is a better guide. During the year it took to record, songs were pouring out of Dylan. His art and career were speeding down the hill. Could he remain upright?

Dylan had handed over control of the career side to Albert Grossman – an abrasive operator who had put together a radio-friendly folk act, Peter Paul and Mary. Grossman had suggested that they release Don’t Think Twice as a single. The trio, however, preferred another Dylan song, Blowin’ in the Wind.

This decision proved to be the making of both acts and a money-spinner for Al Grossman. Dylan’s new manager had changed his new charge’s publisher after hearing Blowin’ in the Wind. Unbeknownst to the songwriter, Grossman had a stake in Witmark Publishing so would be greatly enriched by Dylan’s impending success.

And that success came quickly after Peter, Paul and Mary took Blowin’ in the Wind to no. 2 in the US. This both established Dylan as a significant songwriter and made the song an anthem for those seeking social change.

Blowin’ in the Wind’s melody is based on Dylan’s own arrangement of the traditional song, No More Auction Block – another song I discussed during my revisit to The Gaslight Tapes.

Fellow folk singer David Blue remembers playing the chords for Blowin’ in the Wind on his guitar in a café while Dylan focused on the lyrics. An hour later, a classic was complete.

Later that day, Dylan played Blowin’ in the Wind for Gil Turner, MC at Gerde’s Folk City, who in turn performed it on stage that night. The audience, which included Joan Baez, responded to the song with wild applause, while Dylan stood smiling and laughing at the back of the club.

Blowin’ in the Wind is a song of questions whose answers are out there for you to catch. Dylan highlights social inequities but also tells us that he’s not the one with the solutions.

The optimism that Dylan captured in his song resonated with many involved in America’s growing social movements, most notably the civil rights campaign. Peter, Paul and Mary played Blowin’ in the Wind before Dr. King’s I Have a Dream speech in Washington.

Mavis Staples said that her father was blown away on hearing the song’s opening line: “how many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?”. He was astonished that a young white man was able to articulate his own experience as a black man too often derisively addressed as “boy”.

The success of Blowin’ in the Wind helped Bob Dylan’s career take off and was the first step in his (ultimately unwanted) elevation to a protest icon. It also reflects how Dylan described his early songwriting. He believed that the songs already existed somewhere in the ether – all he did was write them down.

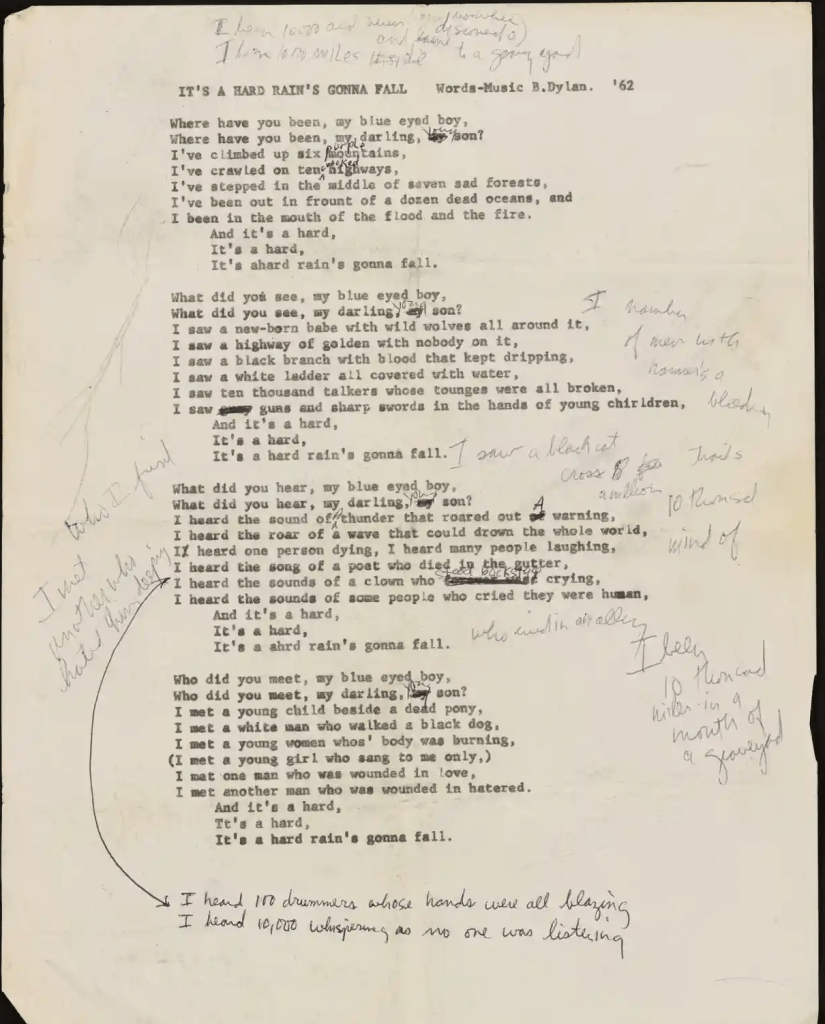

The title of The Freewheelin’ might not just be about Dylan’s career – it may reference that free flow of songs torrenting out of him during 1962. He even said of A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall that each line was the start of new song but he knew he’d never have time to write them all.

Instead, Dylan’s cascade of symbolism-soaked opening lines became a single epic that transformed the idea of what a song could be. After his first ever performance of A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall at Carnegie Hall, the audience was stunned into silence.

Dave Van Ronk – who had told Dylan that Blowin’ in the Wind was a “dumb song” – had to go for a long walk after hearing Hard Rain. When Allen Ginsburg heard it, he realised that the poetic torch had passed to a new generation and cried.

The question and answer format of Hard Rain is based on Scottish folk ballad Lord Randall. But Dylan wrote and recorded it in early December 1962, just before that UK visit where he learned those British and Irish standards from Martin Carthy.

Dylan recorded Hard Rain in one take. He didn’t even feel the need to correct the mistake of singing “what did you meet?” in the fourth verse and I like the slight laugh as he corrects it to “who” when he repeats the line. But you can hear why he felt that he otherwise nailed the take.

Hard Rain starts off quietly but Dylan’s guitar playing and singing gradually get more intense as things build to a climax. Despite the song’s apocalyptic parade of grotesque and grim images, the conclusion of Hard Rain is hopeful, almost euphoric in its stance again the darkness of the world: “I’ll stand on the ocean until I stand sinking and I’ll know my song well before I start singing.”

Hard Rain is singular, astonishing achievement. It describes the shattered civilisation whose failings Dylan will protest in song over the coming years. It also foreshadows the rich, layered language he will use to explore his inner world when he tires of finger pointing. But for now, he’s still got a lot of fingers to point.

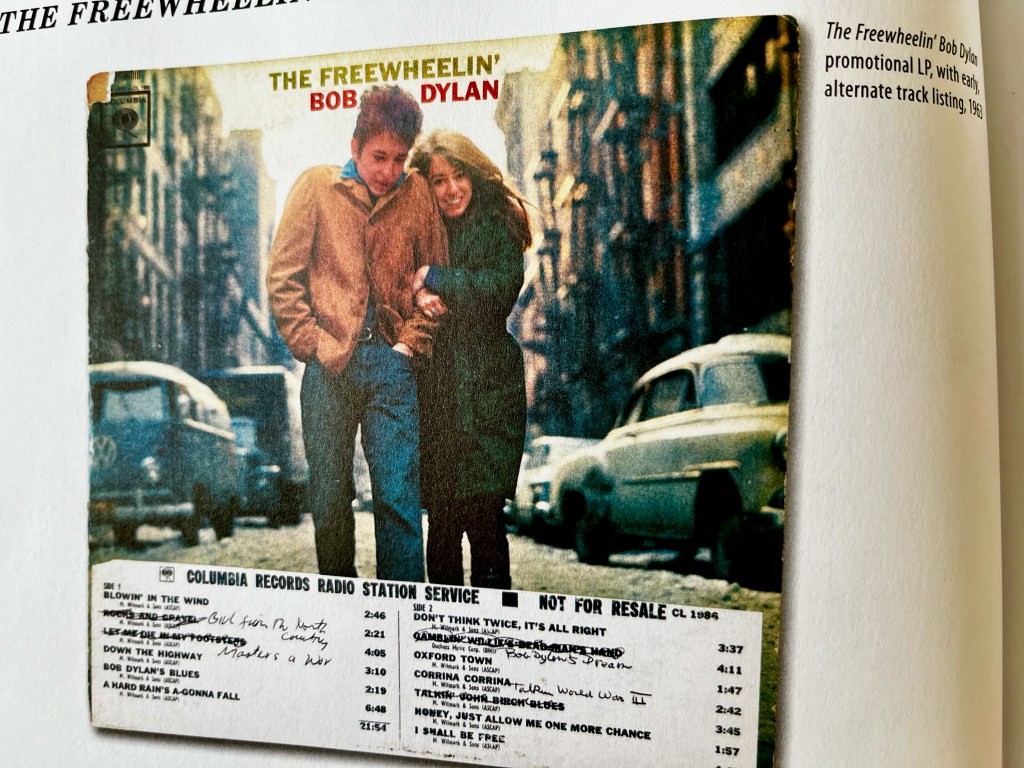

Bob Dylan’s second album is such a freewheelin’ record, there’s an earlier version of it that features four different songs. Although Columbia Records destroyed most of these pre-release copies, a few still exist with one later selling for $35,000.

The late change was all due to one of the deleted tracks, Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues. CBS Television executives had banned Dylan from playing the song on the Ed Sullivan Show, a story I recounted in my revisit to the Brandeis University bootleg.

This hardened his record label’s own opinion that the song was potentially libelous and they forced Dylan to cut it from the upcoming album. Though he resented being censored, the singer used the opportunity to replace songs he had recorded during the previous year with newer material.

Around this time, Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman pushed out John Hammond – the man who signed him to Columbia and produced his debut album – with whom he and Dylan frequently clashed. In his place came jazz producer Tom Wilson, who initially thought “folk music was for the dumb guys” but was won over by the strength of Dylan’s lyrics.

Dylan and Wilson first worked together on April 24th 1963 in an incredible session that produced those four new songs for the album, including Girl From the North Country and Bob Dylan’s Dream. The latter was the last song recorded for The Freewheelin’ and is based on Lord Franklin’s Lament, another song learned from Martin Carthy.

Dylan shifts the original’s setting from the cruel, frozen Arctic to a soft-shuffling train that lulls him into youthful nostalgia. Though written when still in his early 20s, Bob Dylan’s Dream is wistful for the past, for times of certainty when it was easy “to tell wrong from right”.

Yet, in cold light of 1963, Dylan had no problem in assuming a solid moral stance. Sensing the growing mood of protest in early 60s America (possibly aided by his relationship with folk queen Joan Baez), Dylan wanted his record to have more finger-pointing songs.

Masters of War is perhaps his hardest-hitting expression of that goal. A brutal unmasking of the military-industrial complex, the song concludes with the most merciless lines he’s ever written:

“I hope that you die and your death will come soon.”

“And I’ll stand over your grave til I’m sure that you’re dead.”

The melody of Masters of War is based on the traditional Nottamun Town, specifically an arrangement by Jean Ritchie. The American folk singer sued Dylan over his appropriation and reportedly received a $5,000 settlement fee.

When making late changes to The Freewheelin’, Bob Dylan replaced the controversial Talkin’ John Birch Society with another talkin’ blues. Talkin’ World War III Blues captures the apocalyptic paranoia of the early 60s but gives it a humourous twist.

Dylan developed the song in the studio and his delivery is often flat. He isn’t yet selling the jokes like he will when he plays it live. Still, the conclusion is great: “I’ll let you be in my dream if I can be in yours.”

Another socially aware song is Oxford Town. Dylan wrote this as a commission for Broadside magazine, who were creating a compendium of songs about James Meredith’s attempts to be admitted to the racially segregated University of Mississippi.

Dylan’s take on this momentous topic is an odd one as he acts as a somewhat standoffish observer of the riots that happened when the white crowds opposing Meredith’s admission fought with the Mississippi National Guard.

Nevertheless, the slight Oxford Town is elevated by Dylan’s lovely vocals and it is an important signal of his upcoming shift into writing about specific events.

Recorded in nine separate sessions that took place over a year, with an ever-changing final track selection and 20+ songs left for the bootleggers, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan is on one hand a loose, mixed-up record.

But it’s Dylan’s debut album – where he cut single takes of songs he barely knew over three short sessions – that’s the real free and easy record. At one point that eponymous debut was going to be called Free Wheeling. By contrast, the time Dylan took on the real Freewheelin’ suggests he wanted to get this one right.

Perhaps the title of this record is as misleading the album cover with its arm-in-arm couple. But by the time of its release in May 1963, Suze Rotolo was back with Bob in the U.S. All those songs about how much he missed her. Bob must be thrilled to have her back, right?

Maybe not. That same month, Dylan performed with Joan Baez at Monterey Folk Festival and began a relationship with her. She may even make an appearance in the lyrics of The Freewheelin’s quirky closer, I Shall Be Free: “She’s a humdinger, folk singer”.

The song is based on the Woody Guthrie song We Shall Be Free, which Dylan’s hero once recorded with Leadbelly, Cisco Houston and Sonny Terry (that’s all of the people namechecked on Song to Woody from Dylan’s debut album).

Dylan’s rewrite embraces Guthrie’s absurd humour while still pointing a finger or two. After a tin of black paint spills over him, I Shall Be Free’s narrator is forced to sit in the back of the bathtub. Though the playful blackface imagery in this reference to Jim Crow-era racial segregation probably wouldn’t fly these days.

Much more modern and potentially ahead of its time is the verse about hair oil where Dylan asks the football man pushing the product on television if they’ve have a version that would work for black people like Martin Luther King, baseball player Willie Mays and jazz drummer Olatunji.

Dylan never played I Shall Be Free live, which seems odd as these talking blues songs tend to play well in front of an audience. As the closing track to a heavy-hitting album, it’s quite lightweight.

In July, with Blowin’ in the Wind riding high in the pop charts, Dylan and Baez performed together again at Newport Folk Festival. Dylan was now a folk icon and with Freewheelin’ on its way to selling one million copies, pop stardom beckoned.

For me, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan contains a handful of Dylan’s best songs, which makes it an essential listen. Yet those heights are rarely approached by much of the rest of the material, which is interesting if unenduring.

This is perhaps exemplified by the forgettable Bob Dylan’s Blues, a song whose title was at one point considered as the title of the album. While that may have been apt for the lovelorn side of Dylan, The Freewheelin’ is a superior indication of how this is the sound of someone who is going somewhere fast.

He just won’t end up there with the same woman on his arm. But that photograph of Suze and Bob, like the best songs on The Freewheelin’, will endure.

What do you think of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan? Is it a bona fide classic or are we still seeing an artist finding his voice. Let me know in the Comments.

P.S. Blowin’ in the Wind is also the basis for one of the greatest jokes on The Simpsons:

Leave a reply to wardo68 Cancel reply