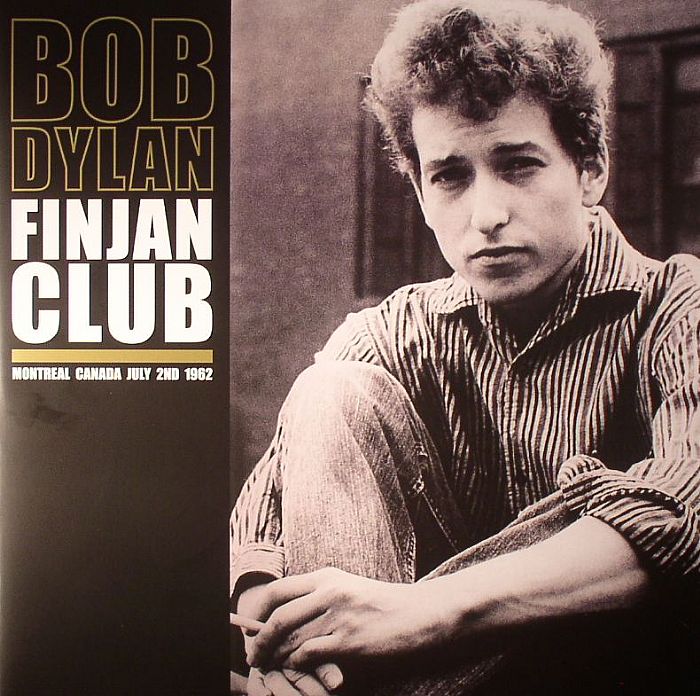

High quality recording of Bob Dylan live in Montreal featuring powerful performances and a lot of faffing.

Share this post with your followers:

“You gonna let this thing run?”

Bob Dylan was performing at Montreal’s Finjan Club on July 2nd 1962 when he directed that question to fellow folk singer Jack Nissenson, who had brought his reel-to-reel tape recorder along to the show.

Dylan was obviously intrigued by the idea of his live set being recorded, having earlier asked Nissenson, “can I hear some of this back after?”.

The latter enquiry followed the show’s opening rendition of The Ballad of Emmett Till, the powerful polemic that Dylan had written about the titular 14-year-old who was lynched by two white men in Mississippi in 1955. Dylan’s performance is serious and strong, as he castigates anyone who “can’t speak out against this kind of thing” with the caustic line, “your eyes are filled with dead man’s dirt”.

With Nissenson’s tape continually running, we get to hear almost every minute of the set, including a false start to Emmett Till. The same happened with the show’s second song, Stealin’, after Dylan realised that his guitar was out of tune. When finally happy with how it sounded, he raced through a lively version of the Mississippi Jug Band tune that he claimed was “one of the earliest songs I ever remember”.

Dylan had performed both Emmett Till and Stealin’ on his Folksinger’s Choice radio appearance earlier that year. But the third song he played at the Finjan Club was a unique selection in his lengthy live career.

After yet another false start where he had spotted that continuously running tape, Dylan played the folk standard Hiram Hubbard, whose grim fate he previewed in his introduction, saying “he was hanged, I guess”. Actually, he guessed wrong as he’ll eventually discover when he sings the line: “it was there that they killed him with rifle bullets three”.

The origins of Hiram Hubbard are vague, but the story takes place in the post-Civil War era and Hubbard’s killers are former rebel soldiers who appear to attack the man for straying on the wrong side of the mountains. Its setting is likely the Appalachians – Jean Ritchie introduced it as a “local murder ballad” when she played it with her fellow mountain native Doc Watson at their acclaimed Folk City live recording from 1963.

It’s unclear how Dylan came to know the song, but he seemed more au fait with its setting than its main character’s specific fate. He adds an appropriate mountain twang to his vocal, while his guitar playing has a spiritual tinge, almost sounding like I’ll Fly Away at times.

More than anything, the tune to Hiram Hubbard sounds a lot like something he’d recently written himself. And so Dylan followed a song he’d only play live just once with one he’d perform throughout the next 60 years.

The Finjan Club was Dylan’s second live performance of Blowin’ in the Wind, following its debut at Gerde’s back in April ’62. At this point, he hadn’t even settled on a title and introduced it to the Canadian crowd as How Many Roads Must a Man Walk Down?

Naturally, there was plenty of faffing about before Dylan got to playing the song. He first requested a C harmonica from someone (possibly Nissensson) then changed his mind and asked for a D. The unknown go-for quipped “scalpel” as he handed Dylan the instrument.

The singer wasn’t done drawing out the build-up to his potent new song. He already appeared to understand its popular potential when he contrasted Blowin’ in the Wind’s socially-minded message with what the audience might expect from more mainstream music.

“This is in a set pattern of songs that say a little more than I love you and you love me, and let’s go over to the banks of Italy and raise a happy family, you for me and me for you,” he asserted before blasting out a superb, long harmonica intro.

Dylan’s guitar on Blowin’ in the Wind is crisp, his pacing steady and his vocal is clear-eyed and certain. He had even added extra lyrics since the Gerdes’ rendition. It is this three-verse version that he’ll capture in Columbia’s Studio A the very next week and use as the opening track on his breakthrough album, The Freewheelin’.

While someone in the crowd enjoyed Blowin’ in the Wind enough to sing along, the applause at the end of Dylan’s performance feels somewhat sparse. However, the Finjan was a small space and it’s likely that there were at most 50 people there to see Dylan play on that summer evening. Among the small crowd was Canadian folk singer Anna McGarrigle, who would soon form the group, Mountain City Four with Nissenson and her sister, Kate.

The club was owned by Montreal-born Niema Ash and her husband, South African musician Shimon. The pair had met and got married when Niema was travelling the world. But a hitchhiking trip around East Africa was cut short when she discovered she was pregnant. After moving back to her home city to have the baby, the Ashes decided to open a new music venue.

The artists they booked to play the Finjan Club were usually not that well known and to save costs the couple used to have the visiting musicians stay in their home. This included Dylan, who Niemi had previously seen performing at Gerdes in New York City, though it wasn’t a great show.

“He kind of limped onstage, whereas the other performers leapt on to it.” she later recalled. The Gerdes’ crowd heckled Dylan for all that pre-song playing around with his guitar and harmonica and Niema remembers one person shouting: “Get on with it – we didn’t come here to sleep!”

The Finjan audience was more patient with his false starts and fidgeting. At one point, someone requested a specific song, but Dylan couldn’t remember the words. He then spent a few minutes half-playing a jaunty guitar arrangement like he was trying to figure out the request, before giving up and launching into a spontaneous rendition of He Was a Friend of Mine.

“It’s nice to be informal” he joked as he began Ric Von Schmidt’s gorgeous paean to a lost friend. Dylan’s Finjan rendition of the song has a little more drive than the restrained version he recorded during the sessions for his debut album. He also improvised some lyrics (presumably because he hadn’t prepared to play it), though this turns out rather clumsy and contributes to a somewhat patchy performance.

It’s the last time Dylan will play He Was a Friend of Mine until 1990, when he returned to the song in honour of his fellow Wilbury at the Roy Orbison Tribute Concert in Los Angeles. Though the unscheduled Bob only played guitar alongside The Byrds having earlier wandered onstage halfway through their performance of Mr Tambourine Man.

Dylan’s casual attitude towards his Finjan setlist makes the performance feel more like a home taped session. Except that the sound quality of the recording is superb throughout. You can even hear Dylan’s harmonica helper rummaging around for the right one.

As the evening progressed, Dylan decided to eschew any expectation the audience might have had of this being a pure folk set. “I’m gonna sing a couple of dirty songs for ya,” he announces before playing the Muddy Waters’ blues number, Still a Fool (often called Two Trains Running on bootlegs of the Finjan Club recording).

Unwittingly anticipating the kind of backlash for not being a folk purist that is very much in his future, Dylan slyly added, “they’re gonna run outta there and say Jesus Christ he don’t sing folk songs…let’s go listen to The Cumberland Three.”

The latter were short-lived group, whose members included Gil Robbins (father of Shawshank Redemption actor, Tim) who would become manager of New York’s Gaslight Café in the late 60s, as well as John Stewart, who became part of the second iteration of The Kingston Trio. Dylan holds up The Cumberland Three as a paragon of the folk revival, a concept of which he already seemed a little contemptuous.

If the Montreal audience had been expecting Dylan to be a clean-cut folkie then they obviously hadn’t heard his bluesy debut album. To be fair, not many people had. Dylan’s self-titled record was released in March 1962 but made little impact in the subsequent months, especially outside of the Greenwich Village scene. He didn’t even play any songs from it at the Finjan.

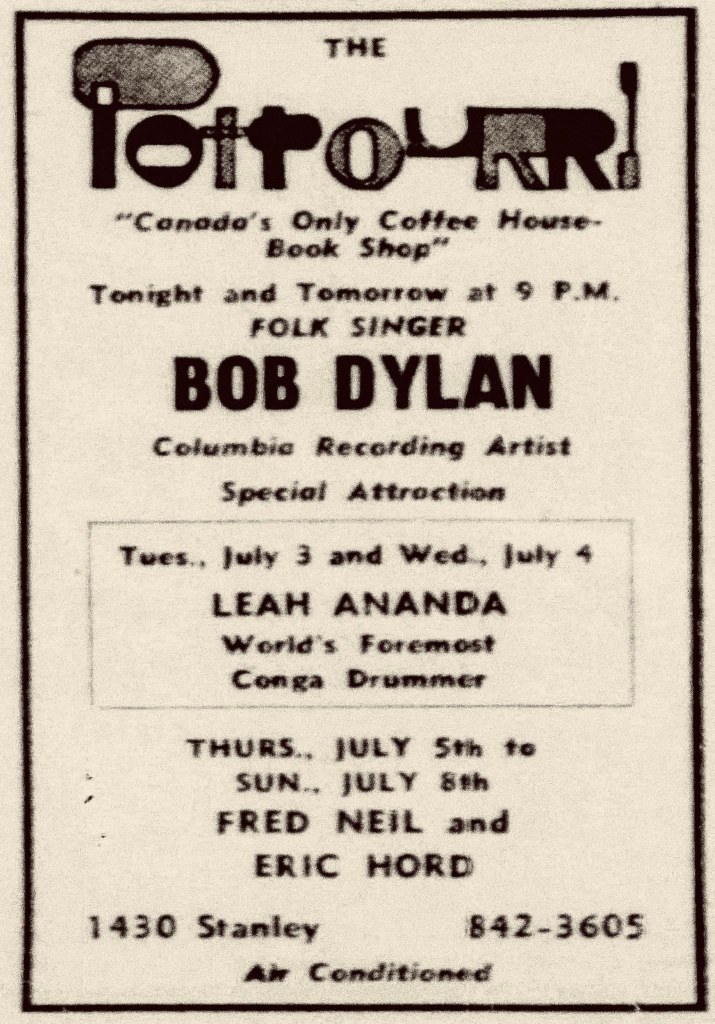

While Dylan was starting to record his follow-up record, Terri Thal (who at the time was married to musician Dave Van Ronk) helped him book some shows outside his regular New York haunts. This included a four-night stint at Montreal’s Potpourri club, which nobody had the foresight to record.

When Niema Ashe saw that Dylan was in town, she persuaded him to stick around for an extra night to play her club. Though she had watched Dylan give up after a few songs in the face of that hostile Gerdes’ crowd, Ashe had liked what she did hear and jumped at the chance to put him on her stage.

Her faith was rewarded by this fine performance, exemplified by his take on Still a Fool. Though he never quite captured it on his debut record, Dylan excels at delivering slow moody blues tunes with great guitar picking and fine vocals, here shorn of the growling affectation of his earlier studio efforts.

As well as being an excellent song, Still a Fool is a portentous choice for Dylan. Muddy Waters wrote it using the same arrangement and melody as his earlier song, Rollin’ Stone. That track title, of course, was picked up by The Rolling Stones (who also recorded an unreleased version of Waters’ song) and then Dylan on his signature song, Like a Rolling Stone.

The Waters original of Still a Fool has three verses, though as Michael Gray pointed out in his book The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, Dylan only plays two of them at the Finjan Club, while adding two more of his own devising. It’s likely he improvised these verses on the spot as the bluesman’s trouble become slightly more disconnected in Dylan’s telling – first he’s with another man’s wife, next he’s the one “put on the shelf”.

Taking existing material and adding to it is one of Dylan’s greatest skills, especially around this period. Rocks and Gravel is a Dylan original that he had already cut during the second Freewheelin’ album session in April 1962. A few months later at the Finjan, he took a couple of attempts to get going, admitting that “I haven’t done this for a while”.

The song – which I covered in more detail in my revisit to The Gaslight Tapes – is essentially a fusion of two old blues songs. Dylan’s alchemy transforms the source material into a taut original that he played for the Finjan audience with rhythmic precision and snatches of falsetto.

That high-pitched vocal style was also on display on Quit Your Low-Down Ways. While he did slip into that debut album gruffness, it contrasts nicely with the howling “pluu-eeeaaa-ssseee” of the refrain. While Dylan recorded a version of this original song during the Freewheelin’ sessions and for his publishing company, Witmark, this was the only time he performed it live.

The same is true of Ramblin’ on my Mind. When he first signed to Columbia Records, John Hammond had given Dylan an advance copy of the label’s new Robert Johnson collection, King of the Delta Blues Singers. It’s likely that Dylan was one of the first people playing those songs live in the early 60s. He had already recorded Corrina Corrina for the Freewheelin’, a song that references lyrics from another Johnson track, Stones in my Passway.

The Finjan Club rendition of Ramblin’ on my Mind is excellent, as he adds some melodic folk textures to the driving blues template. Halfway through, he changes the arrangement, opting for a sparer, bass-led style while varying the tempo and his vocals and generally having a lot of fun with the song.

The final song in the Finjan set is Muleskinner Blues, one of Jimmie Rogers’ Blue Yodel series. True to form for the evening, Dylan took his time getting to the right key and failed to land the first yodel. But after a brief pause, he eventually nailed it though he then stopped playing and the tape cuts off soon after.

Rogers had long been a major influence on Bob Dylan and he had previously been recorded playing Muleskinner Blues on a couple of home tapes back in 1960. He’ll try another Blue Yodel at the end of the decade when he’s messing around in the studio with Johnny Cash.

In the late 90’s, Dylan will curate a Jimmie Rogers tribute album, featuring Van Morrison, Willie Nelson, Alison Kraus, Bono and more. And of course, Dylan’s most recent album, 2020’s Rough and Rowdy Ways is named after a 1929 Rogers’ song.

Nearly 60 years before that, way back at the beginnings of what will be a long and storied music career, the Finjan Club recording allows us to witness the early fumblings of an artist who just seemed happy that someone is interested enough to record him.

But we can already hear that when he’s not messing around (and even when he is), the power, precision and playfulness of Dylan’s performances marked him out for greatness.

What do you think of Bob Dylan’s 1962 performance at the Finjan Club? Let me know in the Comments below.

Leave a comment