Five of the songs on Blonde on Blonde feature a bridge. By my count, just one – Ballad of a Thin Man – does on Bob Dylan’s previous two albums combined. Which makes me think that Dylan wanted his seventh LP to be more of a pop record.

And it’s not just the bridges. Blonde on Blonde has more sing-along choruses than before and the lyrics are more direct expressions of love, longing and leaving. The core of Blonde on Blonde is pop music. But this is Dylan, so the result is naturally unconventional.

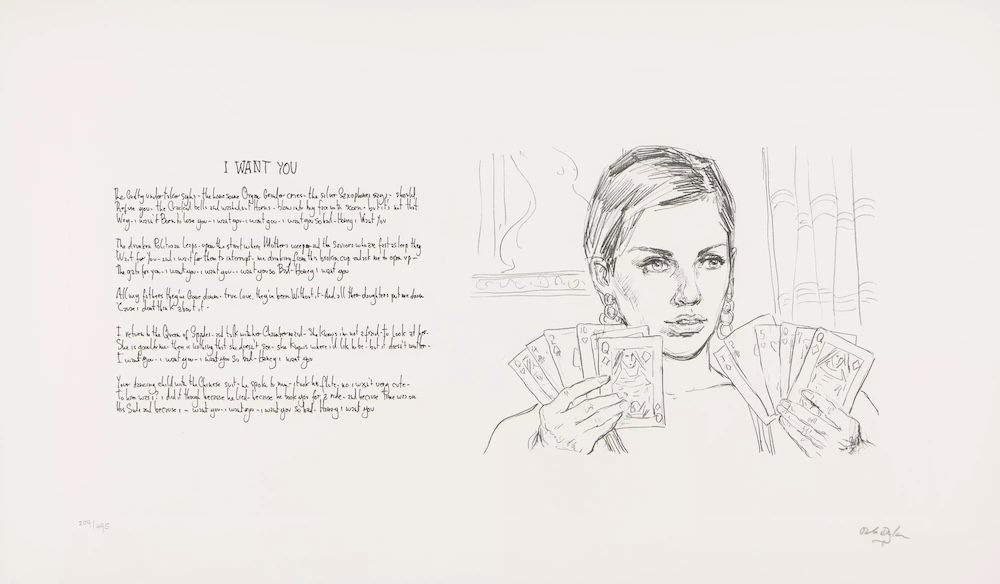

I Want You is about as conventional as Dylan gets. Sure, the verses are filled with oddball characters who could be castoffs from Highway 61 Revisited. But the chorus? “I want you so bad” – jeez, just go ahead and say what you feel Bob.

In his early black and white days, Dylan wrote topical songs that were sincere and forthright. But his love songs back then were layered with light and shade. On Don’t Think Twice, you know it really isn’t Alright. Of course, that was more a breakup than a love song, as is the first recording that Dylan completed for Blonde on Blonde.

One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later) is an apology of sorts for the end of an affair and the mistreatment that occurred within it. Joan Baez is a likely target for the contrition after Dylan’s 1965 UK tour, during which she felt suddenly ostracised. But as we’ll see with most of Blonde on Blonde’s love songs, Sooner or Later also functions as part of a collective address to all of Dylan’s former lovers.

If the lyrics stemmed from an ill-fated relationship, Sooner or Later’s recording was also born of frustration. In January 1966, Dylan was in Columbia’s Studio A in New York with most of The Hawks – part of his new live backing band since August 1965 – and a few other players, but not getting near the sound he wanted.

Sooner or Later took 19 takes though to be fair to the musicians, the song Dylan turned up with was half-baked, without a hook and with ever-evolving lyrics. Eventually, the group found its groove and crafted a classic together.

The highlight of Sooner or Later is Paul Griffin’s piano playing, which begins to build in the lead-up to each chorus before letting loose as Dylan sings the title (in reverse). The Harlem-born Griffin had previously played on records by Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin and had been collaborating with Dylan since Bringing It All Back Home. He had originally honed his keyboard skills in church and on Sooner or Later his ecstatic playing has a divine touch.

Released as a single a month later, the song was only a modest hit in the UK and failed to make the Billboard 100. But Dylan’s biggest disappointment was with the rest of the New York sessions, where he tried and failed to capture several other songs.

Dylan had a particular sound in his head – a specific quality that would eventually crystalize on Blonde on Blonde’s quintessential pop song, I Want You. But as he prepared for yet another tour, it remained out of reach.

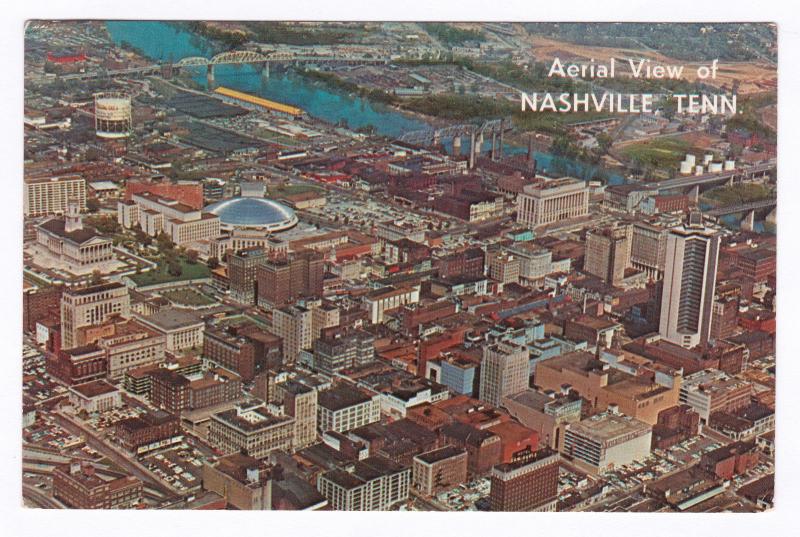

The problem, Dylan decided, was the other musicians. While he enjoyed playing live with The Hawks, they weren’t what we needed in the studio. So producer Bob Johnston came up with a solution that would unearth that elusive tone. It was time to take these pop songs to the home of country music.

Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman didn’t want his charge to record Blonde on Blonde in Nashville and barked at Johnston, “Suggest it one more time and you’re fired.” But with Dylan doubtful about whether his New York musicians could help him capture his inner music, the producer put his job on the line.

Johnston risked the wrath of Grossman by once again conveying the calibre of the players he knew in Nashville. Dylan was intrigued. It helped that he already knew one of them – Charlie McCoy, who showed up during the recording of Desolation Row, picked up a guitar and improvised the lush Latin licks that decorate Highway 61 Revisited’s closing track.

Showing up and nailing a song is what these Nashville musicians did for a living. A typical session lasted three hours, in which time the band would expect to complete half a dozen songs. Day one with Dylan would prove to be anything but typical.

Some of Nashville finest session players went to Columbia’s Studio A in the city at 2pm on Feb 14th 1966, signed their union cards and…sat around waiting. Dylan’s flight was delayed and when he finally arrived after 6pm, he went straight to his hotel to finish writing lyrics.

The musicians spent more than six hours getting paid good money to play cards and ping-pong. Though Al Kooper, Dylan’s regular collaborator since the recording of Like a Rolling Stone, may have regretted cutting short his first ever menage á trois in order to make it to Nashville on time.

The first Nashville session finally got underway after 9pm with Fourth Time Around. After a few takes Kooper nervously noted that Dylan’s homage to / pointed dig at The Beatles sounded so like Norwegian Wood, the Fab Four might sue.

Dylan wasn’t worried, assuring the organ player that it was The Beatles who were copying him. When John Lennon heard Fourth Time Around, he assumed lines like “I never asked for your crutch, now don’t ask for mine” were caustic warnings against imitating Dylan’s style.

Whether Fourth Time Around is a Beatles piss-take or homage is ultimately less interesting than hearing how Dylan and this group of musicians he’d never played with before gradually coalesced to create a light, delicate song.

A particular highlight of Fourth Time Around is the acoustic guitar arpeggios played by Wayne Moss and Charlie McCoy. Once again, like on Desolation Row, McCoy imbues a Dylan song with an unexpectedly vibrant Latin feel.

Dylan and his band would later blast through several superb takes of Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat, a song initially attempted in New York. Though the singer was content with these fresh Nashville efforts, the master would wait for another day.

Finally retiring late that night, the Nashville musicians were astonished by Dylan’s lack of productivity. Yet the third song they played that day showed they were dealing with a different kind of talent.

During those frustrating Blonde on Blonde sessions in New York, Dylan tried 14 takes of a song slated as Freeze Out. Not only was he was still working on the lyrics of what would eventually become Visions of Johanna, he was unhappy with the music coming from his studio band.

Drummer Bobby Gregg’s struggles to land on a satisfactory tempo were especially exasperating. Johnston’s solution to Dylan’s diagnosis was proved more than correct by the Nashville session that captured the master take of Visions of Johanna.

After a brief harmonica intro, Kenny Buttrey introduces a stuttering snare, which soon settles into a perfectly paced march that keeps the song’s midnight meanderings on track.

Buttrey’s tempo is more than ably supported by Joe South’s thrumming bass line that Al Kooper described as “very important” to the song’s rhythm. Meanwhile, Kooper’s organ flickers and shivers, illuminating the shadows cast by Visions of Johanna’s nocturnal milieu.

The story goes that Dylan originally wrote Visions of Johanna during the blackout that affected most of the US northeast in late 1965. As ever with Dylan, this fact has been contested by some and never fully confirmed by the man himself.

But the legend is worth printing because it fits with Visions of Johanna’s feel of the night, of regular life suspended, hanging hesitantly somewhere outside the glow of candles and whispering voices.

The song’s strange characters are inert, uncertain, waiting – like Beckett’s pair of mystery tramps – for something to happen. Even the narrator is continually distanced from the reality in front of him by “these visions of Johanna that conquer my mind”.

Who is Johanna and why does Dylan keep refocusing on her despite the more palpable presence of the delicate, mirror-like Louise? Joan Baez thought it might be her given their partly shared names and that she was in the audience when Dylan first performed the song.

Naturally, Dylan wasn’t telling, nor did he deign to explain the song’s other enigmas:

“Jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule”

“The ghost of ‘lectricity howls in the bones of her face”

“Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial”

Whatever they mean, Visions of Johanna’s words are intoxicatingly inexplicable and charmingly mischievous. This is the most inviting, least sinister of the worlds Dylan created during this era. You wouldn’t mind if the lights never came back on.

I first heard Visions of Johanna on the Biograph compilation, which was a solo acoustic cut from the infamous 1966 UK tour. The song really suits this spare, quiet arrangement.

So, it was remarkable when I later heard what the full band added to the atmosphere on the Blonde on Blonde version. Aside from the stately rhythm section and Kooper’s organ, Visions of Johanna is also laced by gorgeous blues licks from Robbie Roberston’s guitar.

Dylan had told the floundering New York players that only Robertson should rock. That’s what happens in Nashville, as the delicate, considered playing of the local musicians provides a compelling foundation while Robertson’s magnetic notes both sustain and disrupt the story’s measured spell.

The Hawk’s guitarist was a road warrior, much more used to strutting on stage than sitting confined to a studio. When Dylan invited Robertson to record Blonde on Blonde in Nashville, he was initially intimidated about playing alongside the local session talent. Visions of Johanna was Robertson’s impressive first impression and he would go on to ascend even further in their estimation as Blonde on Blonde took shape.

Robertson had been in New York when Dylan failed to capture a satisfactory take of Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat. After those decent day one takes of the song in Nashville, Dylan was happy to wait until the second set of Nashville recording sessions for Blonde on Blonde. These took place in March 1966, after Robertson and Dylan had left the city for yet another series of live dates.

Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat uses the template laid down by Lightnin’ Hopkins’ Automobile Blues to once again disparage that socialite type so brutally rebuked on Like a Rolling Stone.

The titular headgear was famously worn by Jackie Kennedy, so Dylan may also have intended some broader social satire. But his target has taken a new lover, so the scorn is traced with envy and regret that he’s not the one donning the hat in an unexpectedly exposed garage.

In these second sessions, Dylan’s Nashville crew really hit the levels of lively driving blues required by the song, while the increasingly assured Robertson tears it up on guitar.

With Dylan, Robertson and Al Kooper becoming ever more comfortable with the Nashville players, the ensemble took just two takes to master the swaggering Chicago blues of Pledging My Time. Based on the tremendous It Hurts Me Too by Elmore James, Blonde on Blonde’s second track echoes that song’s theme of waiting for a woman who is currently with another lover.

An overdub allows Dylan to use his harmonica in an immediate call-and-response with his own vocals. But the main man’s dual prominence is matched by Robertson’s fiery licks and a stomping piano from Hargus ‘Pig’ Robbins, a Tennessee-born player who had lost his sight as a young child after accidentally stabbing himself in the eye with a knife.

Not to be outdone by his fellow musicians, Dylan ends Pledging My Time with a screeching harmonica solo that amplifies the lyrical distress and devotion. At the other end of the album, we finally get to hear Charlie McCoy play his preferred instrument and his style is a marked contrast.

Inspired by Memphis Minnie’s Me and My Chauffeur Blues, Obviously Five Believers is a fun platform for McCoy’s controlled bluesy harmonica blowing. Dylan urged his band to get the song done quickly and, after an initial breakdown, they nailed it in four takes.

If Dylan didn’t seem too fussed about Obviously Five Believers, it proved an extremely significant song for Robbie Robertson. He later said that his solos on the song earned him the full respect of his Nashville counterparts. Quite an achievement for Robertson, given the calibre of these guys and the musicians with which they were used to playing.

Just before Dylan and his band of Nashville players were about to record Rainy Day Woman #12 & 35, McCoy suggested a new drum part for the song’s introduction. Drummer Kenny Buttrey quickly worked it out and soon Blonde on Blonde’s memorable opening was in place.

Earlier, Dylan had played the song on piano for producer Bob Johnston, who remarked that it sounded like a Salvation Army band. Next thing, McCoy was making late-night calls to his contacts, trying to rustle up a horn section.

Rainy Day Woman is the epitome of a group of musicians in full creative flow, firing out ideas and executing them with exuberance. They cut the track so quickly that Robertson missed the recording, having gone out for a pack of cigarettes.

The whole atmosphere of the recording is so raucous, with much laughter, screeching and whooping that tales of who imbibed what and when are routinely relayed and denied. Given the song’s lyrics, this feels appropriate.

Rainy Day’s refrain of “everybody must get stoned” earned the single a ban on numerous radio stations, which didn’t prevent it reaching no. 2 in the U.S. Billboard chart. But while it’s obviously a knowing nod to drug taking, I also think the words run a little deeper.

Rainy Day Woman is a reaction to Dylan critics. They’ve stoned him (in the biblical sense) for not being the protest icon they need. But for him, doing what he believes in is something to be proud of. Better get stoned than be the one doing the stoning.

In Nashville, Dylan was once more following his own nose and inhaling the vibes of the players around him. While the wider rock world was looking to India and the American West coast, Dylan ploughed into country on Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again.

On the final master of Mobile each instrument weaves its way through the song’s seven minutes, forming a glorious coherent whole. But getting to this point was a struggle. Prefaced by waiting.

The Nashville players were getting used to Dylan spending hours at his hotel working on lyrics while they got paid to twiddle their thumbs. But a 4am call to start work followed by three hours on just one song must still have come as a surprise.

Stuck Inside of Mobile is another of those Dylan songs where the narrator is trapped in a strangely uncomfortable world filled with perplexing characters. I first heard it on the Hard Rain live album and it’s remained a favourite since then.

The lyrics are such a mouthful that Dylan often struggled to squeeze them in to the tempo of the music. Over the long night’s 20 takes, the pace of the song changed repeatedly until the band finally settled on a country gallop that works with the words.

Though Mobile is a team triumph, it’s worth highlighting the interplay of Al Kooper’s organ and Joe South’s guitar. This understanding between one of Dylan’s inner circle and a Nashville stalwart represents the alchemy that occurred from this blending of worlds in Studio A.

The man who most helped to mix this musical cocktail was Charlie McCoy, who directed Rainy Day Woman’s impulsive brass section and made another unique horn-based contribution to Blonde on Blonde.

On November 22, 1965, Bob Dylan married Sara Lownds under a Long Island oak tree. It was a quiet event that the wider world only learned about a few months later. Dylan’s new status can be felt on Blonde on Blonde’s love songs, but mostly in his typically unconventional way.

For a newly wedded guy, Blonde on Blonde is more about the end of past relationships, like Dylan is putting his exes to bed (so to speak). One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)’s potential parting shot to Joan Baez is one example. Another is a companion piece that shares Sooner or Later’s theme of breakups and parenthetical title.

Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine) opens with a devastatingly dismissive opening line: “You say you love me and you’re thinking of me, but you know you could be wrong.” It also contains echoes of an older Dylan song like Don’t Think Twice with its bravado in the face of a relationship breaking down.

But here that bluster is not just in the lyrics, the music is inappropriately jaunty. This feeling mostly stems from Charlie McCoy’s brass playing. The multi-instrumentalist Nashville player contributes a bleating trumpet line on Most Likely. And if Al Kooper’s story is true, he played it in a most extraordinary way.

McCoy played bass guitar on Most Likely and when the brass was required, he picked up the trumpet and played both instruments simultaneously. Kooper recalled Dylan staring “at him in awe”.

I have a strong connection to Most Likely as the first Bob Dylan song I knowingly heard when as a young teen I decided to check out my older brother’s copy of the Before the Flood live album.

It’s also a song that’s stayed with Dylan, who made it a regular part of his Rough and Rowdy Ways setlists from 2021 to April 2024 and included it on Shadow Kingdom, his striking 2021 reinterpretation of his older songs.

There’s another parting of ways on Just Like a Woman where Dylan sings in one of his finest crooner moments: “I believe it’s time for us to quit”. The suggestion this was aimed at ex-lover Edie Sedgwick came from the wonderful line, “her fog, her amphetamine and her pearls.”

But Just Like a Woman’s most interesting set of lyrics once more raises the spectre of Joan Baez: “When we meet again, introduced as friends, please don’t let on that you knew me when I was hungry and it was your world.”

While one of Dylan’s best-known songs, Just Like a Woman isn’t among my personal favorites. But the band’s playing is elegant, Charlie McCoy’s acoustic guitar arpeggios are gorgeous and there’s that great Dylan vocal. So, y’know, it’s still good.

If Just Like a Woman can be a little too leisurely, Absolutely Sweet Marie is enhanced by its strutting tempo, with Kenny Buttrey propelling a somewhat slight song to great heights with his punchy drum patterns.

Al Kooper said of Buttrey’s playing, “the beat is amazing, that’s what makes the track work”. Remarkably, the band nailed the master on just the second complete take.

It’s another song of lost love, or more accurately in this case, thwarted lust, as Dylan spouts innuendos about “beating on my trumpet” or coining another famous new aphorism (“To live outside the law you must be honest”) before moaning, “where are you tonight, sweet Marie?”.

If Dylan was using Blonde on Blonde to close the book on his past, he devotes the epic climax of the record to his future, as Sara finally takes centre stage.

It’s past 4am in Nashville where Bob Dylan and his sleepy band are partway through a song of indeterminate length. A tired Charlie McCoy is finding it hard to stay focused as Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ seemingly endless verses keep spilling out of the wide-awake singer.

For hours the musicians had waited in now-familiar fashion while Dylan worked relentlessly to embellish and refine an epic ode to his new wife. By the end of his endeavours, he would rate Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands as “the best song I ever wrote”.

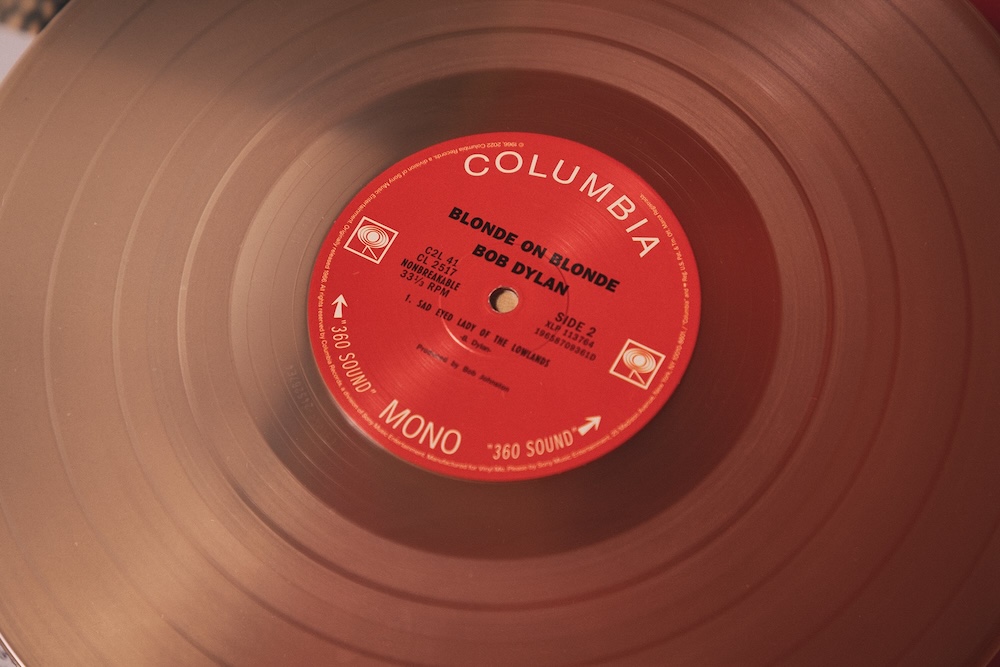

Dylan’s song for Sara runs for more than 11 minutes, occupying an entire side of Blonde on Blonde’s two vinyl discs – rock’s first major double album. But, as previously discussed, the love songs on the album’s other three sides seemed to be about anyone but his new wife.

We get hints of their story on Temporary Like Achilles, where Dylan sings of waiting in frustration for the person he’s in love with. “You know I want your lovin’ / Honey but you’re so hard.”

This could reference that Sara was married to photographer Hans Lownds when she and Dylan first met, while he was with Joan Baez. The singer’s anguish on Temporary Like Achilles is accentuated by Hargus ‘Pig’ Robbins’ woozy piano that reels and lurches like a barroom full of heartbreak.

If the love interest in Temporary Like Achilles sounds irretrievably unavailable, the same was not true for Sara. She soon left her husband, and she and Dylan attended the wedding of her friend Sally Buehler and his manager, Al Grossman in late 1964.

Dylan didn’t want to openly acknowledge this new relationship when his record label asked him to include a woman on the front of Bringing It All Back Home. Perhaps conscious of his Freewheelin’ frieze with Suze Rotolo, Dylan made the-now Sally Grossman his co-star.

Sara would soon be immortalised by Dylan as the woman with the “mercury mouth”, “eyes like smoke”, “face like glass” and “ghostlike soul”. Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands references her father’s “sheet metal” business, her “magazine husband” and her interest in “gypsy hymns”.

Dylan himself confirmed the subject of Blonde on Blonde’s epic finale a decade later, on another album closer, Desire’s Sara: “Stayin’ up for days in the Chelsea Hotel / Writin’ Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands for you”.

In Nashville, Dylan had prepared his band to play Sad-Eyed Lady by mentioning two verses “then we’ll see where we go from there”. Drummer Kenny Buttrey recalled the musicians building after the second chorus assuming the song was about to end. But Dylan kept going.

At the end of five long verses and accompanying choruses, producer Bob Johnston thought the song was “one of the prettiest things I’d ever heard in my life”. Tom Waits would later compare it to Beowulf, saying “The song is a dream, a riddle and a prayer”.

Sad-Eyed Lady’s hypnotic, nocturnal mood keeps you engrossed throughout its long running time. Buttrey’s stuttering drums prod and rouse, Joe South’s bass is the steady tock of a midnight clock, while Al Kooper’s bleary organ weaves magic behind Dylan’s ceaseless singing.

But it’s the words that enthral and not just the florid depictions such as “warehouse eyes”, “matchbook songs” and “geranium kiss”. The constant repetition of “with” and “and” as the lady’s list of traits and travails unfolds creates anticipation for the next startling image.

When you listen to Blonde on Blonde on vinyl, the exclusivity of that fourth side adds to effect. Your immersion into the song and devotion to its subject is only interrupted by the crackle of the runout groove and the cranking of the tone arm as it finally settles back to its resting place.

In 1966 Bob Dylan left the comforts of New York, where he had recorded all his previous records, and headed to Nashville in search of a sound. Years later he’d describe it as “that thin, that wild mercury sound” and hail its exemplar as I Want You.

I Want You was recorded during Blonde on Blonde’s last session, finally ending the frustration of Al Kooper. The organist typically hung out in Dylan’s Nashville hotel room, transcribing songs as the writer completed them, before teaching them to the musicians waiting at the studio.

Kooper loved I Want You and had come up with an arrangement that he was dying to try out. But every time he suggested recording the song, Dylan put him off, “just to bug him” according to Al.

When they finally got to I Want You, Kooper’s idea was blown out of the water when Wayne Moss played a 16-note run on his guitar during one of the takes. The astonished Kooper asked him if he could repeat the feat and when Moss did, they had found I Want You’s buoyant hook.

Like on Stuck Inside of Mobile, the various musicians play the song with remarkable cohesion. Over two months, Dylan and his band had melded in a fluid whole and crowned their last day of alchemy with the quicksilver sound you can hear on I Want You.

For Dylan, this was the purest expression of desire that he had yet committed to record. Those three simple words of the title are repeatedly sighed in the chorus before he adds the almost-adolescent “so bad”.

As with Temporary Like Achilles, it’s likely about the wait for Sara to separate from her husband. But now, he finally had two of those things he wanted: the woman he loved and the sound that had been resonating in his brain.

All Dylan needed next was to get some degree of normality back in his life. But at the completion of Blonde on Blonde, he was on the road again, off on that punishing UK tour where jeering audiences drove Dylan to distracted exhaustion.

What happened next became the stuff of legend. The mysterious motorcycle crash, the unclear injuries and the stark retreat from public view after five years of being one of the world’s most scrutinized icons.

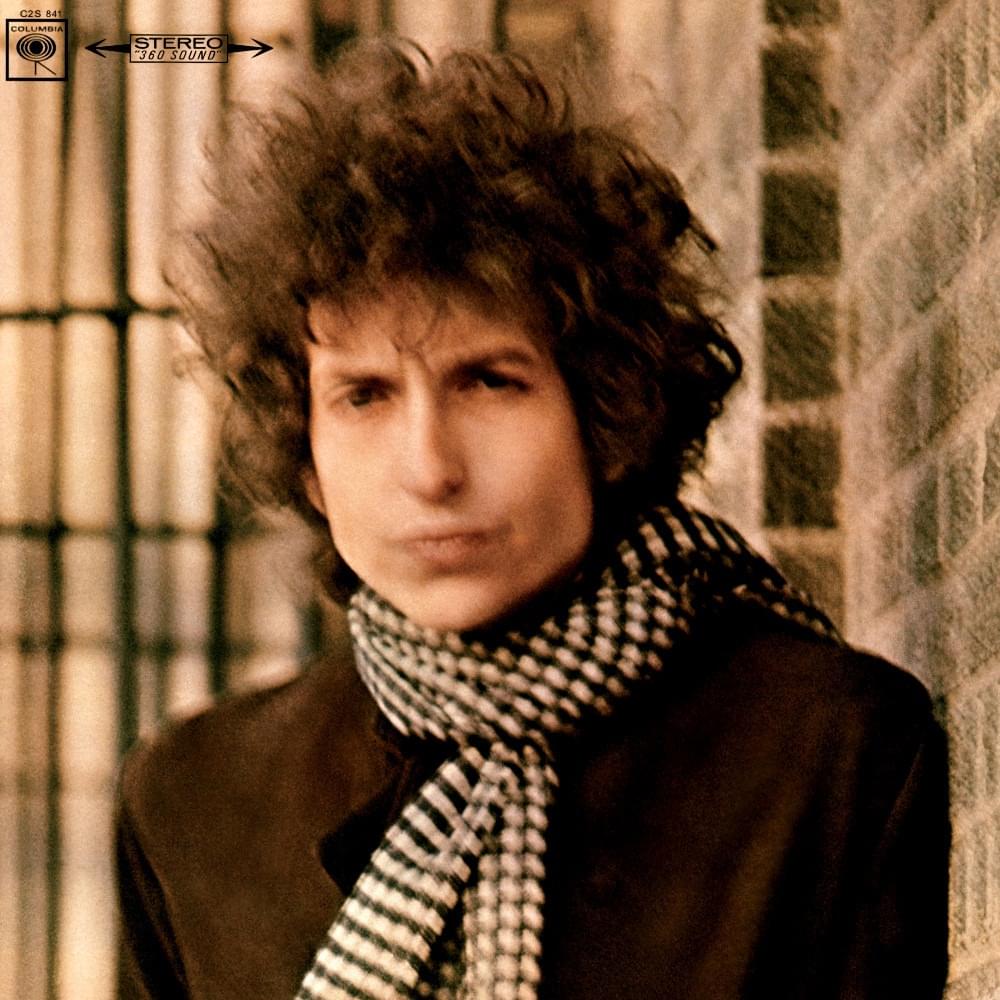

But with Blonde on Blonde, Dylan left a record of such substance it could fill any void. Even the cover – an unconventionally out of focus image of the singer looking distant and pensive – incited speculation over its meaning.

Photographer Jerry Schatzberg recalled the shoot taking place outside during winter. He was so cold that his shivering hands struggled to keep the camera steady. Hence the occasional blurry shot, one of which Dylan decided should be the cover.

At the start of this revisit to Blonde on Blonde, I posited that Dylan was interested in making a pop record. If he believes that I Want You – the most commercial-sounding single of his career so far – was his sonic holy grail then maybe I’m not too far off.

Blonde on Blonde is a great pop album but it’s also so much more than that. In its twinning of New York and Nashville, the folk and rock stylings of its singer and the band’s country and Southern blues backgrounds, Dylan made a record that still sounds like nothing else.

Blonde on Blonde also marks the end of the first phase of Bob Dylan’s music journey. In just a few years he tore through popular culture, shifting from troubadour to protester, icon to pariah, folk singer to pop star.

We have reached the end of an era. But this is Bob Dylan. He gets more than one.

What do you think of Blonde on Blonde? Let me know in the comments.

P.S. If you want to go deeper into the background of Blonde on Blonde, I recommend Daryl Sanders’ comprehensive account, That Thin Wild Mercury Sound. It was an essential resource for this revisit.

Leave a comment