We all know the infamous one-word biblical epithet bestowed on Bob Dylan’s 1966 electric tour of the United Kingdom, as captured in The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: LIVE 1966 – The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert. But my personal favourite review of Dylan’s controversial rock formation came from a young man interviewed after the Newcastle show, who said in a broad Northern English accent: “Bob Dylan was a bastard in the second half.” Which does suggest that at least he enjoyed the first half.

With our benefit of perfect hindsight, it’s easy to look down on those who booed and jeered the future, like the Parisians who objected to the atonal rattles of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. But it’s worth trying to revisit that other country of the past and understand its differences. Some of those present at Dylan’s 1966 UK concerts may not have been familiar with his most recent records. At a time when cultural proliferation was dependent on the sluggish spread of expensive physical media, it’s likely than some fans were just discovering Dylan’s earlier sides. The Times They Are a-Changin’ didn’t make the UK album charts until mid-1964 – more than a year after its release. That record’s title track was a top ten single hit in April 1965. So, it’s not too surprising that many who turned up to see him in concert were expecting the somber, protesting Dylan.

It’s a measure of their open-mindedness that most of them appeared to enjoy the acoustic first half of his shows. Ever the contrarian, Dylan’s seven-song solo set featured nothing from before his March 1965 album, Bringing It All Back Home. Yet every acoustic number at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall is performed to reverential silence and greeted with enthusiastic applause. In particular, the conclusion of the epic Desolation Row receives a rapturous reception. Though nothing can top the previous September’s show at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, where Dylan played the song for just the second time and a woman greeted its conclusion with a wide-eyed cry of “it’s so groovy”.

That LA show took place just days after the release of Highway 61 Revisited, the record that Desolation Row closes. While some people in the UK were obviously still catching up on Dylan’s output, enough of the late spring of ’66 audiences would have been familiar with Dylan’s new material, especially as his sixth LP had peaked at number four in the UK album charts over the recent winter. But even that wouldn’t have helped as Dylan previewed three songs from his yet-to-be-released seventh album, Blonde on Blonde. While you can’t read too much into a crowd’s silence, you do sense that, despite not being familiar with the song, they’re in thrall to his hushed witching-hour storytelling on Visions of Johanna.

Even if you suspect that the crowd is somewhat subdued, perhaps they’re matching the mood of the performer. Dylan’s vocals are oddly hesitant during the opening song She Belongs to Me, while his guitar is disagreeably frenetic. It’s All Over Now Baby Blue lacks a certain vim, though it always does when you remember the charged version he played for Donovan in a hotel room, as captured in the documentary, Dont Look Back. Dylan was often downbeat ahead of the first half of these shows, as if reserving his enthusiasm and energy for the electricity to come. But there’s also a marked contrast in the Free Trade Hall versions of these two songs from that earlier Hollywood Bowl show, where his voice is brighter and his phrasing clear and controlled.

Acoustically, Dylan seems most passionate during his newer songs. He performs a lovely version of Just Like a Woman with a soft mountain folk guitar intro, while any Beatles fans present may have raised an eyebrow at hearing Fourth Time Around and its nod towards Norwegian Wood. Despite this, some critics seem so determined to contrast themselves with the original naysayers that they now denigrate Dylan’s 1966 solo performance. Robert Christgau said, “the folk set stinks”, declaring it “arty, mannered, nervous”.

I just don’t hear that. No matter how he felt about going out alone to play those songs, Dylan was enough of a professional, with enough live shows under his belt, to deliver a consummate, effective and always interesting performance. In Manchester, the hazy hush of his delivery adds to the mood and mystique, especially on those new songs. The audiences at the Free Trade Hall, London’s Royal Albert Hall and most of the other venues on Dylan’s grueling 1966 schedule appeared to agree. As Dylan’s spell-binding rendition of Mr. Tambourine Man, complete with unbridled harmonica solos, closes the show’s first half, maybe our “Dylan was a bastard” friend should have simply been content to leave before the band plugged in and the unrest began.

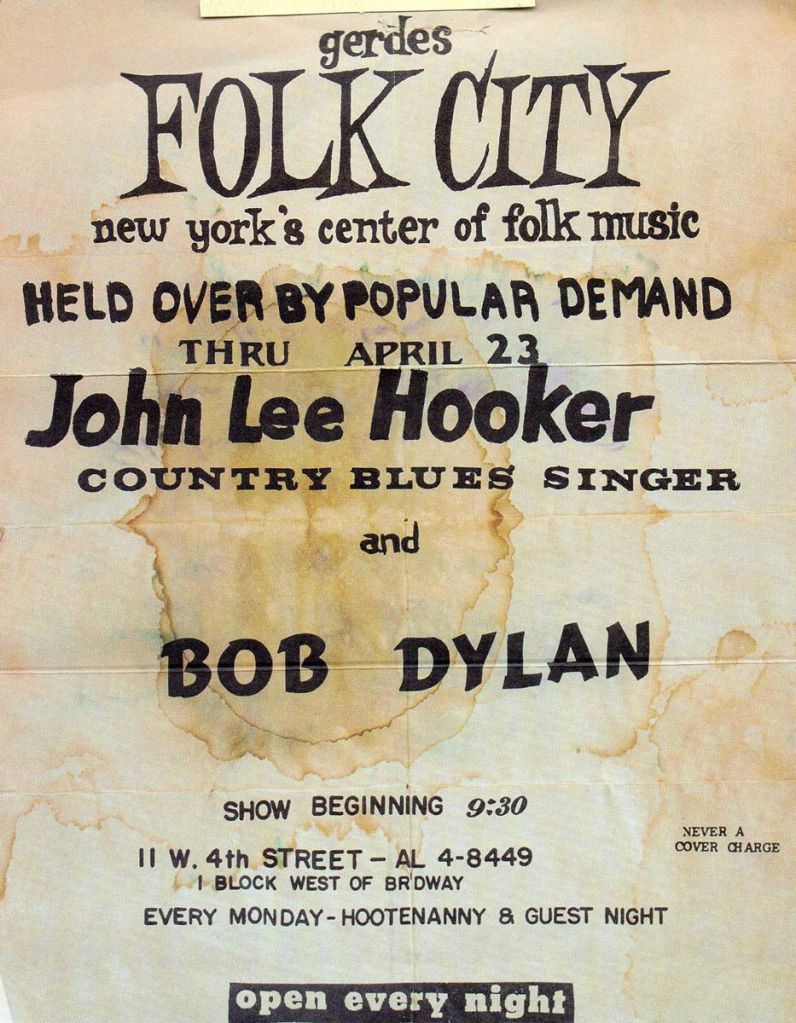

In his riotous (if unimaginatively titled) autobiography Life, Keith Richards mentions how when his guitar idol John Lee Hooker first started playing with rock musicians, he split his set into acoustic and electric halves. And guess what? The crowd booed when he plugged in. Dylan’s first paid gig was a two-week support slot for Hooker at Gerde’s Folk City in New York, so he likely paid close attention to the bluesman’s subsequent doings. On his 1966 world tour, Dylan once more borrowed from the past and elevated it to new heights.

He had plenty of hints that the electric second half of his new live show would not go down well, from the evidence of John Lee Hooker to his own experience at Newport Festival the previous year. But he in no way tries to mitigate that with his choice of opening song. Tell Me Momma will never feature again in Bob Dylan’s career. After this tour, he won’t play it live nor record it in the studio. Its sole purpose appears to have been to introduce his backing band, The Hawks, in the most belligerent way possible.

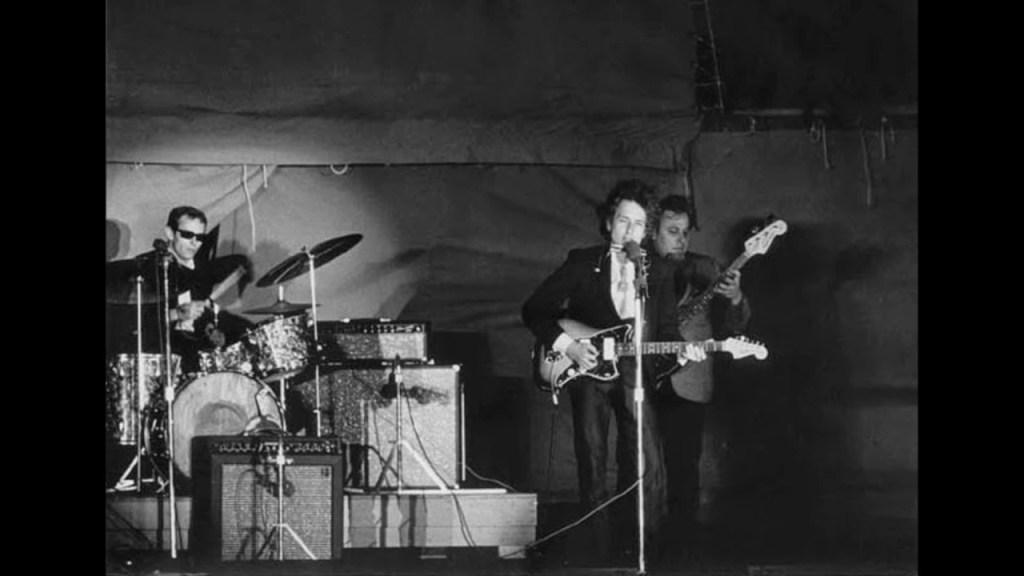

As the second half of the Free Trade Hall set opens, we hear the band warming up and a crackle of anticipation from the audience. Hazy guitar riffs gradually come together before Mickey Jones’ chunky drum beat kicks Tell Me Mama into life. It’s fast, loud, fun and kinda dumb. In short, it’s rock’n’roll. And that’s not what these people came to hear. But the conclusion of Tell Me Momma is greeted with polite applause.

The real discontent comes about halfway through the electric set and centres around Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat, a new song whose introduction is interrupted by catcalls and coordinated clapping. This brawling pub rock music and its apparently superficial, fashion-focused lyrics must have appalled those folk fans hoping for some quiet substance. The response to Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat is the most mixed so far and the yells and jeers become more intense.

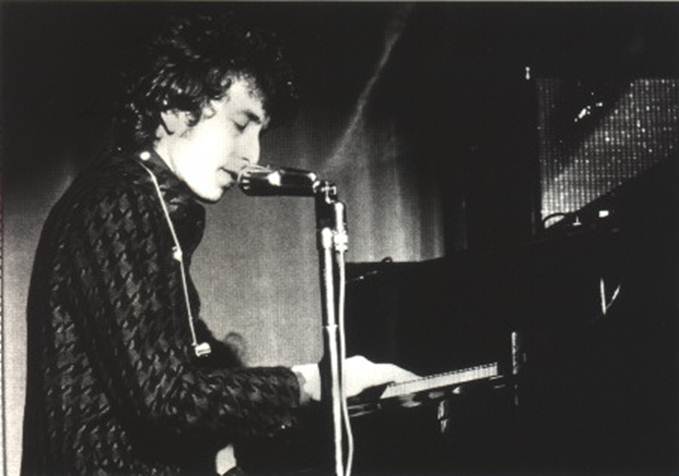

It may be a mistake to assume the audience was offended by the song’s lyrics, as they likely couldn’t make them out. A common complaint voiced years later by those who were there is that the sound quality, especially the vocal mix, was terrible. John Cordwell – who claims to be the show’s most infamous catcaller – has remained a Bob Dylan fan and now enjoys listening back to the electric Free Trade Hall performance. Though as he later insisted in an interview with the journalist Andy Kershaw who tracked him down: “it didn’t sound like that”. For later listeners, the most useful indication of how the show sounded in person like comes during the penultimate song, Ballad of a Thin Man. Dylan has moved to the piano and presumably switched mics. His vocals are swampy, like he’s singing/shouting from inside a safe.

While some of the dissent was likely premeditated and coordinated, maybe we can cut other disgruntled Free Trade Hall attendees some sound quality-related slack. They simply weren’t able to appreciate what we can hear more clearly today on the cleaned-up, soundboard recordings. What the ’66 audience often missed out on was a relatively new combination of musicians hitting top form as Dylan and The Hawks went back to some of his early classics and made much mischief with them.

“It used to be like that and now it goes like this.” It was the perfect line for the occasion. Concise, clear and completely downplaying the havoc Bob Dylan and the Hawks are about to wreak on I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met). This version of Dylan’s acoustic classic isn’t as much of an assault as the electric set opener, Tell Me Mama. But the Free Trade Hall take on I Don’t Believe You is still an all-enveloping, resounding experience.

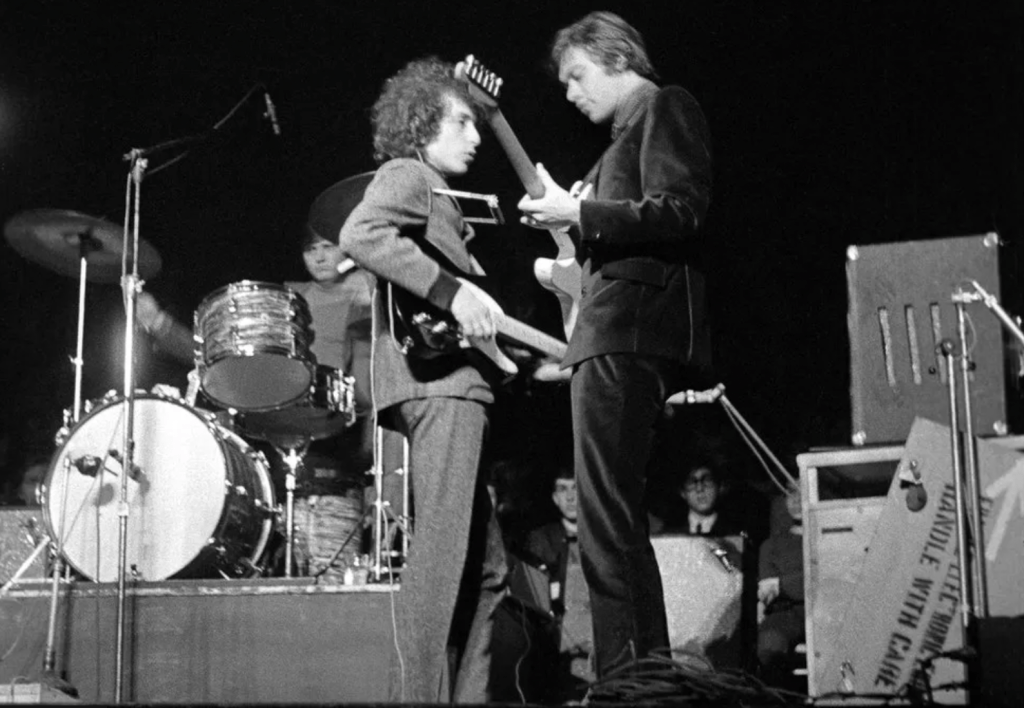

It’s the sound of a band that Dylan first discovered when his friend John Hammond Jr. was recording So Many Roads. This ground-breaking folk-rock record featured The Hawks as Hammond’s backing band. The group had originally come together as support for Ronnie Hawkins, a rockabilly singer who first recruited fellow Arkansas-native Levon Helm as the drummer for his band in 1958. A year later, The Hawks moved to Toronto to capitalise on their sizable Canadian following. When all the Hawks but Helm moved back to the US, he and Ronnie recruited Canadian replacements: Robbie Robertson, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson. This new combo split from Hawkins in 1963 and continued touring as Levon and the Hawks. And after recording with Hammond, an impressed Bob Dylan came calling.

At first, Dylan just added Helm and guitarist Robertson to a band that included organist Al Kooper and Harvey Brooks on bass. This was the Hollywood Bowl line-up, one of the few occasions where the electric set didn’t seem to generate as much animosity from the crowd. Helm was in tremendous form throughout: a dynamic presence on I Don’t Believe You, setting the pace on From a Buick 6, adding portentously thunderous drums on Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues and creating a triumphant groove for the finale of Like a Rolling Stone.

But Kooper and Brooks decided to quit the band after being spooked by the hostile audiences. You can get a better sense of what they were facing from an audience tape of the show at Forest Hills Stadium in New Jersey on August 28th 1965. The jeers, boos, cries of “too loud” and most notably the repeated, loaded chant of “we want Dylan” give a taste of the general unrest among the crowd that day. At one point, you can hear what sounds like a surge of movement. Kooper remembers people trying to get onto the stage and claimed that one person knocked him off his chair.

When the US tour resumed in late September, the rest of the Hawks had replaced Kooper and Brooks. But, by the time Dylan and his band reached Manchester in May 1966, the original Hawk, Helm had also quit the tour. Having broken free of Ronnie Hawkins, he was reluctant to be part of someone else’s backing band – especially one that was booed every night. He ended up working on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico until Robertson persuaded him to rejoin the band (still lower case at that point) at their Big Pink retreat in Woodstock in late 1967.

Helm’s replacement Mickey Jones provides a thunderous introduction to the electric set’s third song. First Dylan teases the hook on his harp and Danko lays down a stuttering bass line. Then Jones rattles his skins and Baby Let Me Follow You Down explodes into new life. Once the gentle Eric Von Schmidt song that Dylan recorded for his debut album, Baby Let Me Follow You Down’s live mutation into a raucous rock song is a knowing act of mischief. Most importantly, it’s a brilliant version. Dylan barks the titular pleas, Robbie Robertson’s guitar solos are searing and Garth Hudson adds a thrilling organ solo. And all the while, Jones moves things along with his driving tempo and monstrous fills.

There’s more willfulness afoot later, just after the crowd’s agitation has been elevated by Leopard-Skin Pillbox Hat. Dylan does the classic teacher move of mumbling quietly to regain their attention then raises the volume to say “…if you only just wouldn’t clap so hard”. Having used his wit to bring some of the audience back onside, Dylan and The Hawks launch into a loud and wailing take on the once serenely sad, One Too Many Mornings. With its crashing drums, swirling organ and bellowed backing vocals, this rocking of one of Dylan’s stillest songs is pure provocation of the Times-era fans. Yet, it’s also a valid interpretation that Dylan had been building to in previous acoustic performances, such as his take on the song at New York’s Philharmonic Hall in 1964.

By now, the Free Trade Hall crowd knows its role in this participatory pantomime and the unrest is building. Soon, words will be exchanged and the volume turned up.

“Judas”

“I don’t believe you…you’re a liar”

“Play fucking loud”

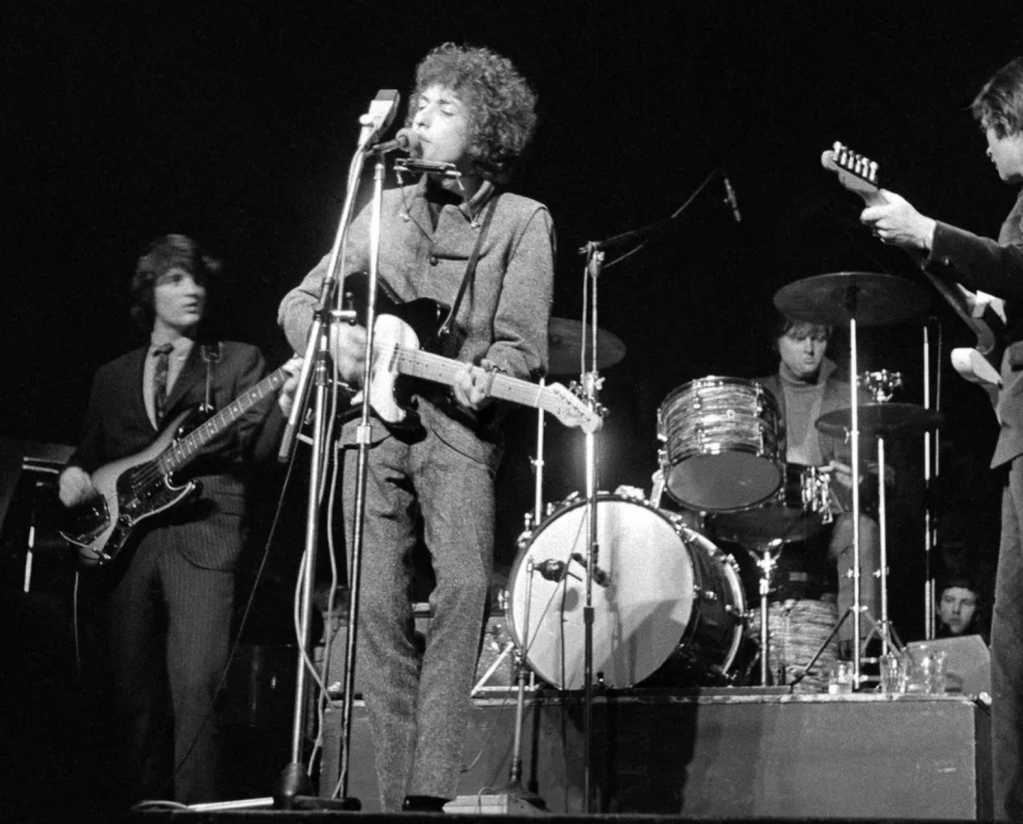

Can you think of another headline act who was heckled and jeered by their own fans just before playing their biggest hit? Such unique mayhem was a result of Dylan – to quote one enlightened audience member interview by Dylan’s own film crew – “just doing what he wants to do.” And after someone in the crowd succinctly summed up their sense of betrayal by his turn to rock, all Dylan really wanted to do was respond with a blistering performance of Like a Rolling Stone.

Ahead of the US leg of this first electric tour, Dylan had addressed his band like they were readying for battle. The stakes felt real. Once of Al Kooper’s reasons for not going over the top again after Hollywood Bowl was that he realised they were due to play Dallas – the site of JFK’s murder most foul two years previously. But Dylan still had brave soldiers on his side, none more so than guitarist Robbie Robertson, who constantly put himself in the firing line with his gutsy blues solos. He’s a powerhouse on the Free Trade Hall version of Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.

And he’s obeying orders and playing fucking loud on Like a Rolling Stone, as are the rest of his comrades. Mickey Jones’ drums are a marching clatter, while Garth Hudson’s organ blares like an air raid warning. As for their leader, Dylan is yelling “didn’t you?” with more disdain than ever before. His rage is palpable, his sense of righteousness apparent in every drawl and sneer. It’s thrilling to behold. Then the noise abates and Dylan snarls a sarcastic “thank you” before leaving the stage. After some general hubbub, the PA system blasts out God Save the Queen, like the old order hadn’t just been blasted away by the previous seven minutes of sound and fury.

Vol. 4 of the Bootleg Series captures an astonishing moment in both Dylan’s career and rock history. And it’s just one of many fractious performances from 1965-66, most of which you can hear on the epic 36-volume complete collection. For years the bootleg of the Free Trade Hall performance was erroneously called the Royal Albert Hall show. The real Royal Albert shows from May 26-27th are worth a listen as a tired-sounding Dylan fires back more retorts to the hecklers. The tour concluded here and while Dylan sounds like he stumbling over the finish line on Like a Rolling Stone, another song is fueled by the rancour. “These are all protest songs,” he sneers ahead of an extra-charged Just Like Tom Thumbs Blues.

Taken individually, none of the electric performances are my favorite version of these songs, but that’s not the point. The awesome power lies in the entirety of the set, its full-throttle defiance and the growing belligerence of the audience. Live 1966 (whichever date you choose) remains an essential document of unusually combative performances – the likes of which we’ll never see again.

What do you think of The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Live 1966 – The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert? If you’ve listened to any of the other 1966 shows, I’d love recommendations of your favourite renditions. Let me know your thoughts in the Comments below.

Leave a comment