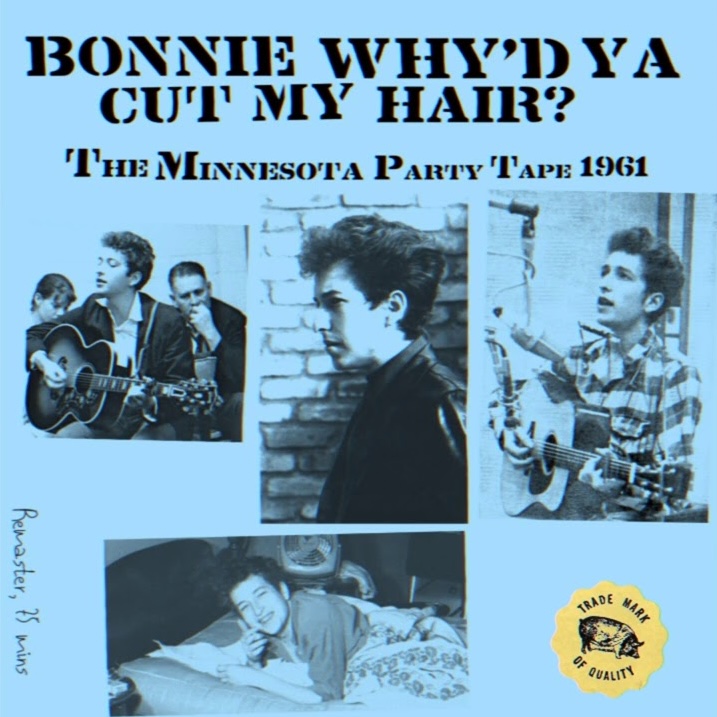

Having spent a few months in New York City in early 1961, Bob Dylan returned to his home state for a short visit in May of that year. Playing songs for a few friends from his university days in Minneapolis, he was keen to show off what he’d experienced since he left. The informal performance was recorded and subsequent bootlegs became known as The Minnesota Party Tape.

“I learned this from Woody. He said I sung it better than anybody”, Dylan boasted before playing Guthrie’s Pastures of Plenty. Like many a traveller returning home with tales to tell, he wanted to portray himself as a big fish when back in the city’s small Dinkytown-based folk pond.

Not only had he spent time with his hero Woody Guthrie, Dylan also integrated himself into the heart of the Greenwich Village folk scene. He was friendly with some of its key figures like Dave Van Ronk, Odetta and The Clancy Brothers, while earning a regular paid gig at Gerdes Folk City, warming up the audience for John Lee Hooker.

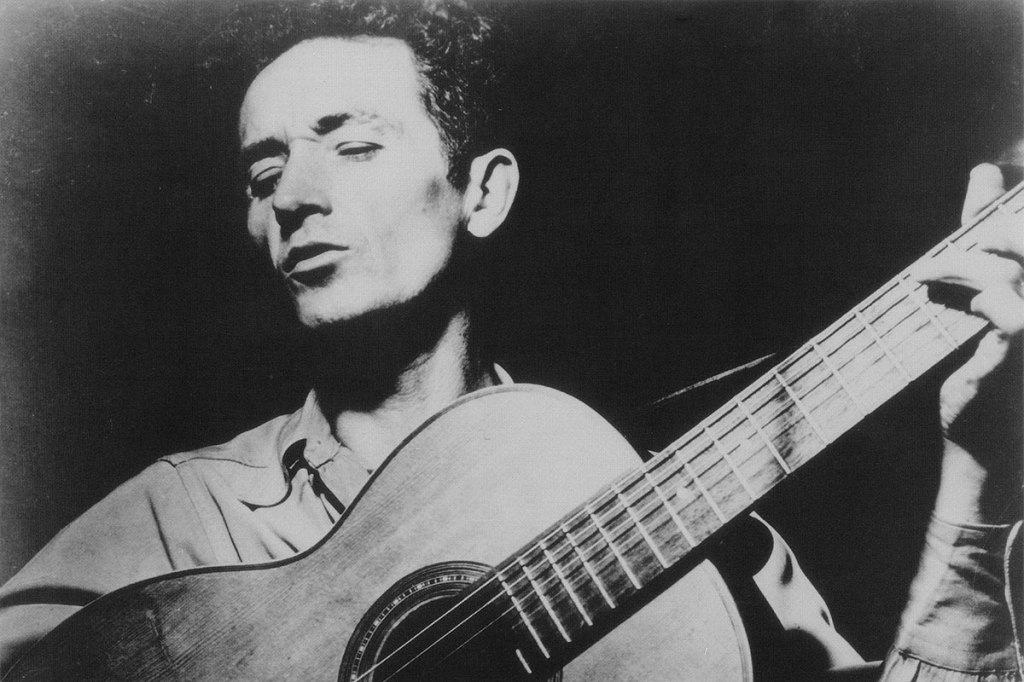

His Minneapolis friends would have certainly remembered Bobby Dylan as someone with a Woody Guthrie fixation. There’s a recording from 1960 of him singing Guthrie’s Jesus Christ in a strangulated voice that’s striving to sound exactly like his idol. In Chronicles, Dylan recalls how a friend called Flo Castner had first suggested that he listen to Guthrie and brought him to her brother’s house to hear Dust Bowl Ballads.

The experience was transformative: “When I first heard him it was like a million megaton bomb had dropped.” From that day on, Dylan devoted himself to playing Guthrie’s songs, dropping most of the other material from his repertoire as he became “Guthrie’s greatest disciple”.

Meeting his hero was one of Dylan’s main objectives when he left Minneapolis for New York in January of that year. Indeed, Van Ronk believed it must have been his main reason, as the city’s folk scene wasn’t exactly flush with money by that point. Within a week of arriving in New York, Dylan made the trek from Manhattan to New Jersey to visit the ailing Guthrie at the Greystone Park psychiatric facility.

The debilitating effects of Huntingdon’s disease meant that Guthrie could barely light a cigarette, never mind play a guitar, and his verbal communication was limited. Yet the pair bonded, though Dylan described his role as “more as a servant…I went there to sing him his songs”.

Occasionally Woody left the facility to spend time at the nearby house of his friends, Bob and Sid Gleason. These gatherings were attended by Guthrie’s old boxcar buddies, the musicians Cisco Houston and Brownie McGhee, as well as the latter’s regular collaborator, harmonica player Sonny Terry, and the younger Guthrie wannabe, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott.

Dylan sometimes managed to wrangle an invite to the Gleasons where he mostly just watched the other musicians, absorbing their songs and styles. He did eventually play himself, some of which was captured on tape, including a captivating performance of Pastures of Plenty, an epic rendition of Trail of the Buffalo (aka Buffalo Skinners). He also played Guthrie’s arrangement of Gypsy Davy and a lovely take on Lulu Belle and Scotty’s 1940 country song, Remember Me (When Candles Are Gleaming), which Willie Nelson would have a hit with in the 70s.

When Dylan returned to Minneapolis and showed up at the home of Jaharana Romney (who was then known as Bonnie Beacher), she remembered him speaking with “the strangest Woody Guthrie-Oklahoma accent.” If his speech was ersatz, the connection was genuine. Though naturally, some of his old friends may have questioned where Dylan’s stories about knowing Guthrie were true.

Romney believed this is why Dylan insisted on taking her out to see Woody at Greystones when she later visited her friend in New York City. Despite being unsettled by the facility’s clanging security doors, she recalled “being awe-struck” by Guthrie and was able to report back to the Dinkytown crew how he and Dylan seemed like “there were very good friends”.

The Minnesota Party Tape starts with Ramblin’ Round and you can hear the shift in Dylan’s delivery from the previous year’s recording of Jesus Christ. While his back-of-the-mouth vocal style references Woody, the imitation has now become more an impression. On Ramblin’ Round, he plays a neat, picked guitar arrangement and a short harmonica intro before singing Guthrie’s migrant chant in a slow staccato style. It’s a calm and assured performance though that Okie-accent affectation does rear its dusty head during the fruit picking verses.

The tune of Ramblin’ Round is adapted from Lead Belly’s Goodnight Irene, which was originally recorded at the Angola State Penitentiary by archivist Alan Lomax and his sister Bess. In the 1940s, the latter performed with The Almanac Singers, alongside Guthrie, who taught her how to play mandolin.

On The Minnesota Tapes, Dylan performs Devillish Mary, a song often credited to Bess Lomax Hawes. It’s most likely a traditional song that Bess recorded, as the Lomaxes often assigned themselves publishing rights over the compositions they captured in the field. Dylan’s rendition is short and lively, singing just a couple of the song’s verses in a wilder, more open voice.

He’s back to the Woody impression on This Train Is Bound for Glory – the traditional spiritual that is referenced in the opening and closing of Guthrie’s autobiography. In Chronicles, Dylan recalled reading Bound for Glory from “cover to cover like a hurricane”. The highlight of this Minnesota Party Tape performance is his chugging harmonica, which speeds up before a crashing conclusion.

Before playing Wild Mountain Thyme, Dylan says, “Here’s a Texas song. I learned this from Woody Guthrie.” If this was in New York, the infamous self-mythologiser would probably have concocted some outlandish story about boxcars and carnivals, but his Minnesota friends were not as likely to be fooled. Besides, the truth is just as remarkable. As is Dylan’s persuasive performance of a song that he will return to almost a decade later at the 1969 Isle of Wight festival.

Dylan is strangely hesitant on a rendition of Guthrie’s most famous song, the anthemic This Land is Your Land. His opening guitar intro sounds a little uncertain and he stumbles over the beginning of the third verse like he momentarily forgot the words. But this is a song he’ll grow into and in just six months, Dylan will deliver a superb version of it at New York’s Carnegie Chapter Hall.

Of course, occasional mistakes are to be expected in this kind of informal, home-taped performance, where the singer was deciding which songs to play as he went along. The recording captured 24 songs and it’s frankly remarkable how he kept them all in his head. The ability to hear a song once or twice and be able to replicate it faithfully is something that many of Dylan’s fellow musicians have often mentioned.

Even knowing that he had this knack, I was still surprised by how he was able to knock off a five-track run of Guthrie’s children’s songs. The Dust Bowl Balladeer began writing and recording music for younger ears from the mid-40s, around the time he started having his own offspring. Dylan plays Howdido, Don’t Push Me Down, Come See, the nipple-obsessed I Want My Milk and Car Car, on which he will duet with Van Ronk at New York’s Gaslight Café later in the year.

Staying on the goofy theme, Dylan had earlier played Guthrie’s Talkin’ Fishing Blues. His delivery was very dry on this sly ode to laziness though things do liven up towards the end. Dylan had performed the song a couple of weeks earlier at the Indian Neck Folk Festival, an event that played a part in the broadening of his influences and repertoire beyond Guthrie.

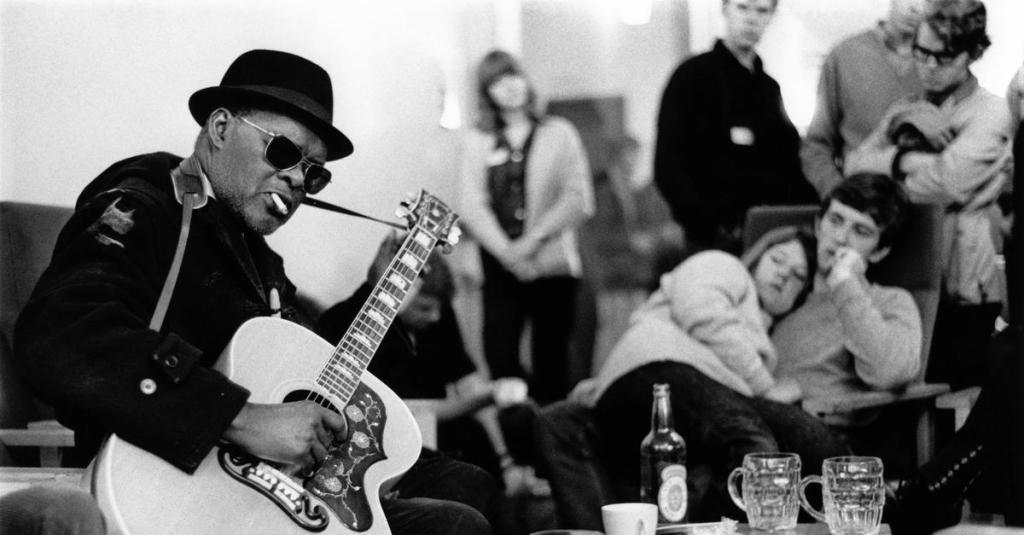

One of the performers that Dylan saw at the Connecticut festival was Rev. Gary Davis. Born in the Piedmont area of South Carolina and blinded by a maltreated eye infection as a baby, Davis played guitar and sang from a young age. His unique finger-picking style became a core component of the Piedmont Blues and he was a mentor to another of the region’s most popular performers, Blind Boy Fuller.

After being ordained in the Baptist church in the mid-30s (hence the Rev.), Davis began focusing more on gospel music. He moved to New York in the late 1940s to play at churches in Harlem, but as the folk revival took off, he found a new audience for his music. One of Dylan’s own mentors, Van Ronk learned songs from Davis and included his arrangement of Samson & Delilah on his 1962 album, Folksinger.

Peter Paul and Mary would also do a version of that song a few years later, which became a hit. While it was technically a traditional song, Davis had claimed the copyright so could later describe his home as “the house that Peter Paul and Mary built” – an experience he shared with Dylan.

The song that captured Dylan’s attention at Indian Neck was Death Don’t Have No Mercy, a bleak Davis original about the brutal grim reaper who “never take a vacation”. Dylan mumbles Davis’ name in his introduction then mentions how the song will “start out in E minor, then go to G and back again.” After a fine fingerpicked intro, he sings in a similar growl to the one he’ll use a lot when recording his debut album at the end of the year.

This song followed on from his Guthrie impression on Ramblin’ Round and it’s fascinating to hear how he switches up his vocal style depending on the song he’s singing. It’s an early indication of how Dylan will change his voice throughout his career.

While his take on Death Don’t Have No Mercy sounds good, Dylan cuts the song short after one verse, saying “that’ll give you some sort of idea how it goes.” He then goes into a song that’s credited as a traditional called It’s Hard to Blind, but is essentially Davis’ Lord, I Wish I Could See. Dylan’s arrangement is maybe a little too jaunty for despondent lines like “nobody cares about me”, but his harmonica interludes are great.

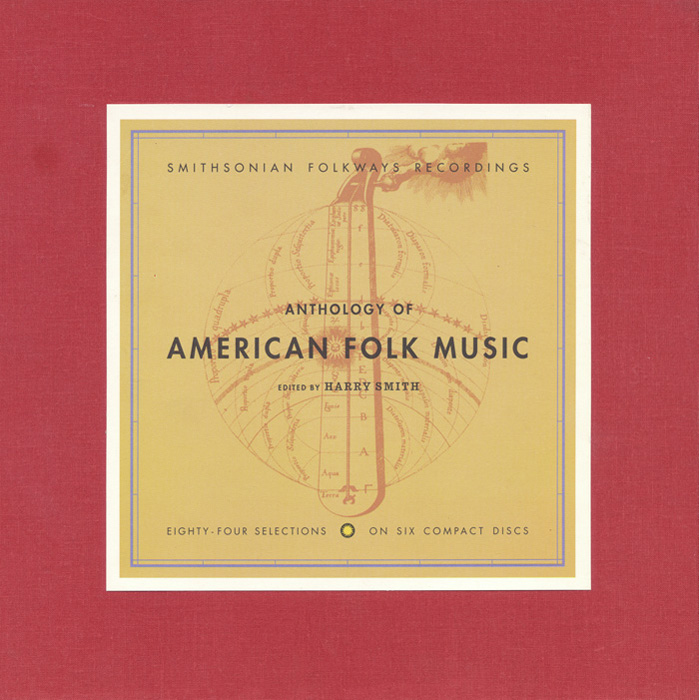

Another huge influence on Dylan around this time was Anthology of American Folk Music, the 1952 three-volume compilation of songs from the 1920s and 30s. The collection was created by Harry Smith from his own collection of 78s, so unlike the Lomax field recordings, the Anthology’s songs were all culled from commercial studio creations. Van Ronk had a copy of the record that Dylan would have heard though, as he later told Rolling Stone, his fellow musicians playing these songs had more of an impact than the recorded versions.

Railroad Boy is a good example of this process. The song appears on Smith’s Anthology as The Butcher’s Boy by Buell Kazee, a Kentucky-born banjo player who sings it in a clear music hall style. Van Ronk regularly played the song during the late 50s, while Irish singer and Clancy Brothers collaborator Tommy Makem recorded a quivering version for his solo 1961 album.

That same year, Joan Baez cut a rendition for her second album but the titular knave became a Railroad Boy, which is what Dylan repeated on his solid Minnesota Party Tape version. By 1963, when another Kentucky native, Jean Ritchie sang a version on her live album with Doc Watson, the title again changed to the song’s most potent line, Go Dig My Grave. That’s the name under which contemporary Irish trad band Lankum recorded their 21st century take, featuring a mesmerising vocal from the extraordinary Radie Peat.

Another song from Joan Baez Vol. 2 that Dylan plays is The Tree They Do Grow High. Though Baez’s album wouldn’t be released until September 1961, Dylan could have heard her play the song in person before then. In Minnesota he adopts a higher vocal register than he typically used on these performances and accompanies himself with an effective mix of picking and strumming.

Yet there’s something about this rendition that falls short – he’s not quite inhabiting the song as he does others on the tape. Maybe that explains why he returned to it six years later when he played it with The Band in the basement as Young But Daily Growin’. Perhaps with time, he can make it his. However, I’m not a fan of the basement take either nor the version he played live at Carnegie Chapter Hall in late 1961.

Another song that would reoccur to Dylan years later is Railroad Bill, a traditional about the exploits of a 19th century train robber, who may be the real-life Morris Slater. Or it could be that he earned the nickname from the song, which may be more plausible for a man named Morris. Dylan recorded a version of this during the Self Portrait sessions in 1970. The fun Minnesota version from nine years earlier is remarkably similar even without the studio take’s barrelhouse piano, as played by Al Kooper.

Some songs from The Minnesota Party Tape stuck with Dylan for a shorter time. Two Trains Runnin’ is a Muddy Waters song that Dylan will return to a year later when he plays the Finjan Club in Montreal. The home taped version is a good spare blues rendition accentuated by raspy but thankfully not too growly vocals and some locomotively-inspired harmonica blasts.

Perhaps more significant is his wild take on Jesse Fuller’s San Francisco Bay Blues. While this isn’t a song Dylan will return to, he will go on to open his self-titled debut album with another Fuller song, You’re No Good. That record also featured Man of Constant Sorrow, which he plays for his friends in Minnesota with a slightly different arrangement to the one that will appear on wax.

The latter song was written by Dick Burnett who was probably the first person to record Under the Weeping Willow Tree, a song largely associated with The Carter Family. Like Burnett, The Carters featured on the Anthology of American Folk Music and the four songs by them included on the collection reflect the outsized influence of AP, Sara and Maybelle on roots music.

It’s no surprise to hear Dylan play one of their most famous songs, the AP-reworked spiritual, Will the Circle Be Unbroken. His Minnesota version is a decent take though he only plays it for a minute. This is another song Dylan will return to in the basement towards the end of the decade, while he’ll also perform this communal classic during the Rolling Thunder Revue in the mid-70s.

Another cut from The Anthology of American Folk Music was James Alley Blues by Richard Rabbit Brown. The title is a tweak on the real-life Janes Alley in New Orleans where Brown was from, located in the same rough part of town where Louis Armstrong grew up. As a performer, Brown was probably best known as a musical boatman who sang songs while rowing tourists across Lake Pontchartrain, just north of the city.

James Alley Blues is an excellent tune, full of tough times, mean women and rent due. Dylan gives it his best grizzled growl, which suits the downtrodden theme while easing up on the intensity of Brown’s version, making it more melancholy than bitter. He also tweaks the final line of the second verse to “There’s too many people and they’re all too hard to please”, a phrase he’ll use on his early, electric single Mixed Up Confusion in late 1962.

This is one of the few signs of Bob Dylan the songwriter on this Minnesota Party Tape. Another hint is his superb performance of Pretty Polly, the traditional murder ballad, whose tune he’ll soon appropriate for The Ballad of Hollis Brown. And in this, Dylan continues to follow in the footsteps of his hero, as the song is also the basis for Guthrie’s Pastures of Plenty.

The Minnesota tape does feature one Dylan original, which comes at the end of the recording after Romney begs him to play it. The story she tells is that Dylan had arrived at her apartment, anxious about the length of his hair as he would be seeing his parents during this trip back to his home state. She gave him a trim though he insisted on her cutting it shorter and shorter.

When more friends arrived, they laughed at the extreme state of his shorn head, which Dylan immediately blamed on Romney. Then he started singing a flippant song about it, “Bonnie, why’d you cut my hair? Now I can’t go nowhere.” Romney obviously took no offence and her cajoling ensured this early improvised Bob Dylan composition was captured on tape.

Perhaps even more interesting is that in his introduction to the song, he talks about doing a “harmonica blow-out solo”. Typically, harmonica players suck in more blow out and you can hear Dylan play this way on a long bluesy harmonica instrumental earlier on the Minnesota Party Tape. But a few people, like one of his heroes Jimmy Reed, primarily blew out and Dylan gradually adopted this style, which helped him stand out among the many harmonica players in Greenwich Village.

Playing harmonica backing for Fred Neil at Gerdes Folk City was one of his first regular gigs in New York. And when Carolyn Hester asked Dylan to back her on the instrument during a recording session for Columbia, he would meet John Hammond who soon signed him to the label. All the pieces were being put in place for Bob Dylan’s breakthrough.

While the songs and stories captured on the Minnesota Party Tape may have been fun for Dylan’s friends back home to hear, they may not necessarily have presumed that he was destined for greatness. He was a decent performer with an interesting – if Woody Guthrie-heavy – repertoire, but even Dinkytown had its share of good players like Spider John Koerner and Tony Glover.

However, the next time Dylan returned home at the end of 1961 and performed on what became known as the Minnesota Hotel Tape, his friends would be stunned by his evolution.

What do you think of the Minnesota Party Tape? Let me know in the comments.

Leave a comment