Revisiting the peak and completion of Bob Dylan’s protest phase.

Share this post with your followers:

“What is this shit?”

That infamous Self Portrait review opener by critic Greil Marcus had been posed directly to Bob Dylan six years earlier.

The cursing question was asked by a friend who had just read the lyrics to the title track of Dylan’s third album, The Times They Are a-Changin’.

A friend and fellow musician from Dylan’s Minnesota days, Tony Glover was in New York to make his own record.

Visiting Dylan in his apartment, he saw the Times lyrics sheet and was particularly unimpressed with the line, “Come senators and congressmen, please heed the call”. Glover asked, “What is this shit, man?” Bob replied, “It seems to be what the people like to hear.” He was right. The Times They Are a-Changin’ would become one of Dylan’s most iconic songs.

At its heart is a simple call for cooperation. Dylan calls on mothers, fathers, writers, critics, those senators and congressmen and society’s other elders to embrace the youth-led change that seemed to be sweeping away old prejudices and practices in early 60’s America. Or at least, to get out of the way “if you can’t lend your hand”.

This new order was symbolised by John F. Kennedy, the youngest ever president of the United States and hero of progressives who had beaten Richard Nixon to the White House in 1960. With The Times They Are a-Changin’ following on from his other protest anthem, Blowin’ in the Wind, Dylan too solidified his place as a liberal icon.

He first played the song live at Carnegie Hall in October 1963 and it became the essential opener to his set for the next couple of years. Dylan said at the time that “my whole concert takes off from there.”

However, a month later, he opened his set with it the day after Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, unsure if its hopeful message was still appropriate. He later said he couldn’t understand why the crowd were clapping or why he even wrote the song.

This disillusionment with the true potential for change was probably not new for Dylan. He had finished recording his third album on the last day of October. If its title and opening song gave people hope, the rest of the record resolutely did not.

The Times They Are a-Changin’ – the song – might be the last time that Dylan ever gave people what they wanted. The Times They Are a-Changin’ – the album – forces them to bear witness to a grim parade of poverty, injustice, murder and despair.

The late addition of Masters of War to The Freewheelin’ helped with Dylan’s desire for more finger-pointing songs. His next record upped the accusatory ante even further. If the Times were supposed to be a-changin’, here he shows how far they had to go.

The hope engendered by the opening title track is immediately dashed by The Ballad of Hollis Brown. It’s a devastating account of a South Dakota farmer mired in poverty and beset by bad luck, that concludes with mass murder.

Even the rebirth of its closing lines – “There’s seven people dead on South Dakota farm / Somewheres in the distance there’s seven new people born.” – can be read equivocally, as there’s no guarantee they won’t be lives of equal misery.

Dylan had been playing Hollis Brown live since late 1962 and the song it’s based on, Pretty Polly, for even longer. On this album version the guitar strumming of his live performances is transformed into a taut-string picking style.

Tom Wilson – now on full-time production duties – wanted a harder guitar sound for The Times They Are a-Changin’ record and pushed Dylan’s voice up in the mix. This austere aesthetic is perfect for relating Hollis Brown’s tragic tale.

Like the album’s title track, North Country Blues opens with the words “Come gather round…” But the song then follows Hollis Brown’s theme of rural poverty with its description of a northern mining town’s slow descent to destitution as the iron ore mines close.

Unusually for Dylan, North Country Blues is written from the perspective of a woman, while the setting and specific details suggest that he drew heavily from things he heard about during his Minnesota childhood. References to “draglines and shovels”, “number 11 is closing” and “cardboard-filled windows” evoke the town in good times and bad, while “The room smelled heavy from drinking” is a superb depiction of the damage done by decline.

I loved With God On Our Side when I first heard it as a teenager. The heavy irony of ending each verse’s litany of historical violence by adding that they were done in God’s name appealed to my burgeoning atheism. When Dylan played it at Carnegie Hall in October 1963, the audience cheered at the end of each verse, demonstrating what an unorthodox message it was back then.

Today, With God on our Side sounds over-wrought and obvious, while its long dreary tune doesn’t help. Dylan co-opted the melody from another song about the dangers of unquestioning patriotism, Dominic Behan’s The Patriot Game. The Irish writer (younger brother of playwright Brendan) publicly called out Dylan’s appropriation – a somewhat hypocritical move given that Behan had based his tune on the English folk song, One Morning in May.

With God on our Side includes the plight of Native Americans – “the cavalries charged, the Indians died” – but doesn’t mention the other major victims of US history. However, Dylan has plenty to say about black civil rights elsewhere, just not in the way many of its supporters may have expected.

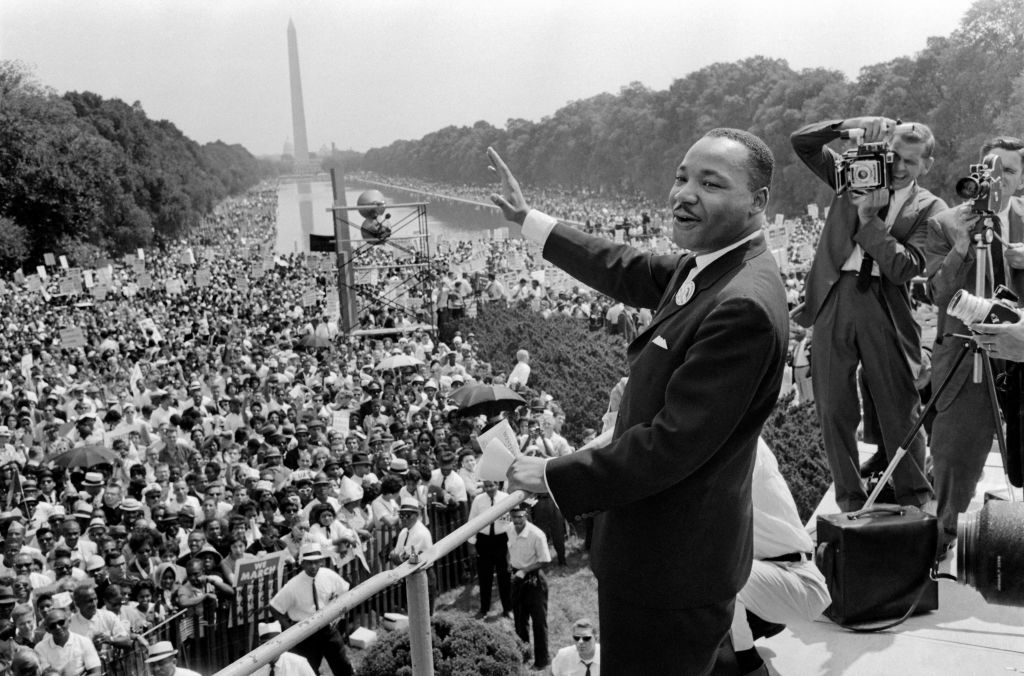

On Aug 28th 1963, 250,000 people marched on Washington demanding better economic and civil rights for African Americans. They witnessed Dr King’s I Have a Dream speech and cheered Blowin’ in the Wind, as sung by Peter Paul and Mary.

But Bob Dylan wasn’t as widely well received.

Where other Dylan songs about violence against black people – The Death of Emmet Till, Oxford Town, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll – take a straightforward liberal approach, in Washington he chose to perform Only a Pawn in their Game.

While ostensibly about the murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, Only a Pawn is more interested in the political profits of fueling racism. It’s ultimately a song more concerned with class than race. Portraying Evers’ assassin as a poor white man who “can’t be blamed” as he was manipulated by politicians, did not sit easily with the audience in Washington that day.

It wasn’t the first time that Dylan had performed Only a Pawn in Their Game in front of a predominantly black audience. Back in July 6th, he had accompanied Pete Seeger and others to a voter registration rally in Mississippi, the state where Medger Evers was born and killed. At Seeger’s urging he played the song, which appeared to be well received.

Certainly, Only a Pawn’s nuanced exposition of how those in power stoke racist fears for their own gain is a message that’s much more accepted and as depressingly relevant today.

On the same day as the Washington march, a judge in nearby Maryland sentenced a white man convicted of killing a black woman. It won’t surprise modern audiences to learn that William Zantzinger (in his song Dylan tweaked the spelling of this surname) only got six months (deferred so he could harvest his tobacco crop) and a small fine for the murder of Hattie Carroll.

Dylan wrote The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll after hearing about the trial. Unlike his take on the Medgar Evers story, he chose to ignore the nuances of this incident in favor of presenting an elementary and emblematic case of injustice. But the song is also much more than a protest piece.

Where Hollis Brown is a news report and Only a Pawn a political point, on The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, Dylan delves emotionally into the life and death of the song’s title character. After opening verses describing the murder and introducing the villain of the piece, the heart of the song is the woman of its title. In plaintive, simple words we get a sense of the small drudgeries and humiliations of Hattie Carroll’s life before feeling the pointlessness of her death.

Dylan had been inspired to introduce more complexity to his songs after seeing a performance of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s Threepenny Opera. In his memoir Chronicles, Dylan discussed how the song Pirate Jenny – sung from the perspective of another woman who had spend her time scrubbing floors for others – opened his mind to what could be done in a song.

He also noted how the song’s titular character often seemed to be implicating the audience in her fate. On Hattie Carroll, Dylan directly addresses his listeners in each chorus, which commands us to “take the rag away from your face”. Push your grief aside as we pursue justice. However, when it fails to be brought to bear, he urges us to feel the full rush of despair in the final chorus twist: “bury the rag deep in your face, now is the time for your tears”.

While many of the protest songs on The Times They Are a-Changin’ are detached descriptions, on Hattie Carroll, Dylan fully grieves her loss and the injustice provided by Zanzinger’s meagre sentence. But there are other reasons for Dylan’s despondency on this record.

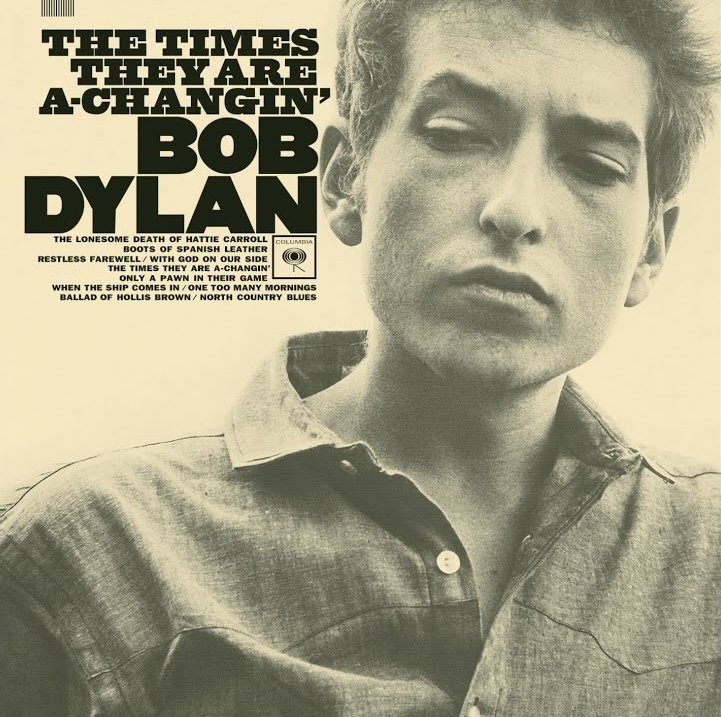

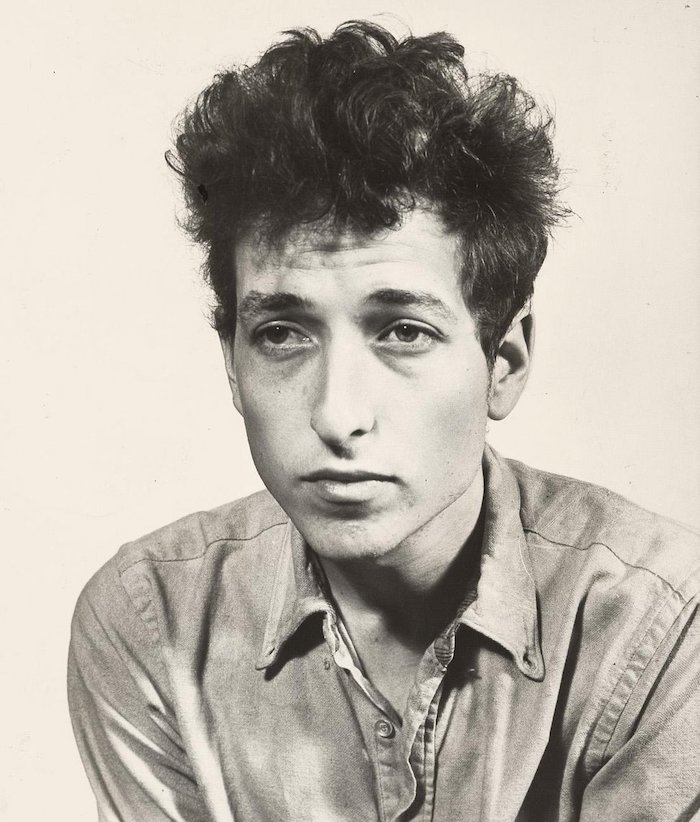

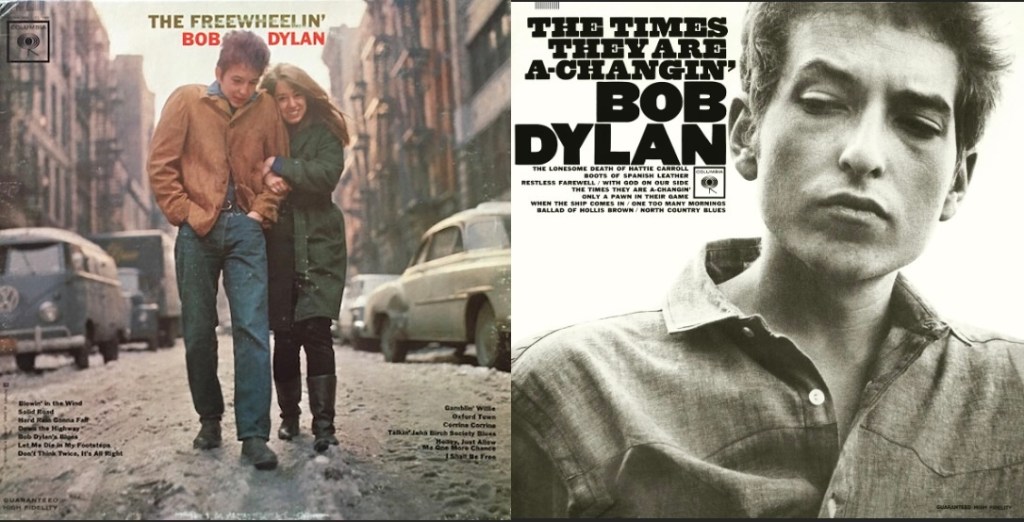

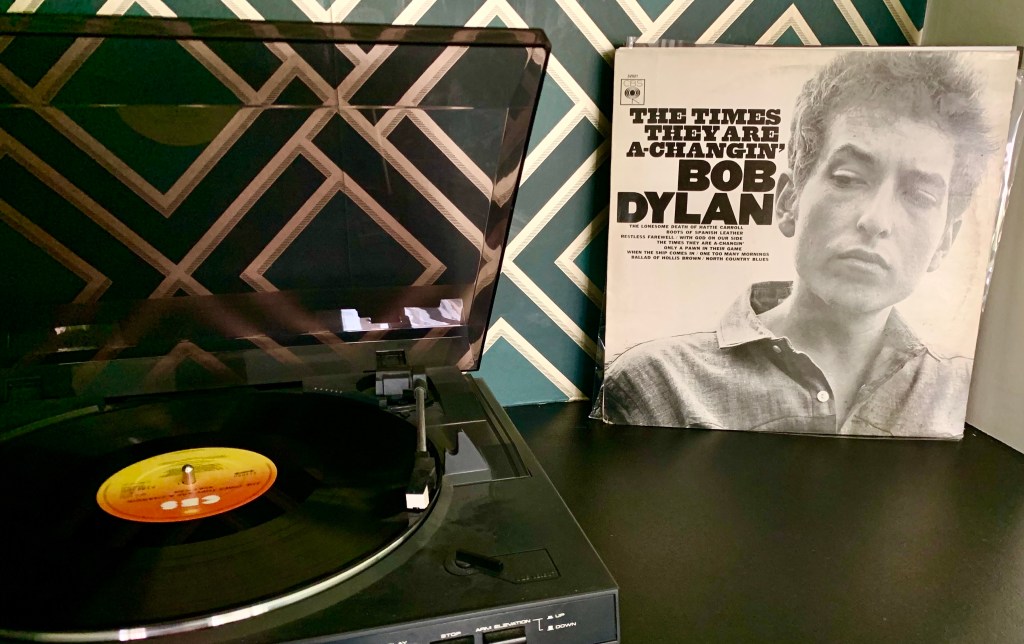

The stark, serious monochrome cover of The Times They Are a-Changin’ provides a notable contrast with the warm glow of The Freewheelin’. Times’ austere Woody Guthrie impression is an accurate representation of the album’s mood.

And it’s the Freewheelin’s cuddled cover star who is partly the reason for this somber tone. Despite Suze Rotolo returning to the US after her year in Europe, she and Dylan went through a bitter breakup that fueled two of the record’s finest songs.

Boots of Spanish Leather is a return to those Freewheelin’ songs about her Italian absence as well as a musical revisit to Girl from the North Country. A beautiful tale told through lovers’ letters, the leaver asks if the other wants a souvenir from her travels. After repeatedly requesting nothing but his love’s return, the traveler finally concedes that she may never come back.

The left-behind lover asks for the present of the title – boots for the bluesman’s broken-hearted road walking. Their country of origin may be a reference to Guthrie’s Gyspy Davy – another song that involves a back-and-forth between former lovers, where the jilted man urges the woman to remove her “buckskin gloves made of Spanish leather”.

One Too Many Mornings is one of my favorite songs on The Times They Are a-Changin’. The lyrics feel intensely personal as Dylan reluctantly lets go of a love affair that has long run its course: “You’re right from your side and I’m right from mine.”

More than the failed relationship musings, the song’s power is its setting: the singer leaving their shared space, stepping out alone into the early evening with only barking dogs for company, compelled to do so by a “restless hungry feeling”.

One Too Many Mornings is the one place on the album where Tom Wilson’s lucid production with vocals to the fore takes a most appropriate back seat. Instead, we get an incredible hushed sound like the stillness of the night with Dylan singing in a quiet, melancholy tone.

After dashing any of the hope built up by The Times They Are a-Changin’s opening title track with a series of songs about injustice, poverty and heartbreak, Bob Dylan reintroduces a fresh spark lit by pure fury.

When the Ship Comes In is an angry escalation of the album’s title song. That was an invitation to be part of the change. This is a warning to get out of the way. And he’s no longer saying “please”. Its plain assertions went down much better when Dylan performed it at The March on Washington than Only a Pawn’s nuances.

Ship has serious Old Testament energy: the winds, birds and fish are on the side of the righteous, there’s a Babelesque confusion of languages and the seas will split so that his enemies “like Pharoah’s tribe they’ll be drownded in the tide”.

All this over a hotel clerk.

Joan Baez claimed that Dylan wrote the song after an encounter at a hotel that refused to give a room to the scruffy singer. Once Baez had secured his entry, Dylan sat at his typewriter and furiously tapped out his vision of vengeance.

If the revolutionary leaning of The Times They Are a-Changin’ was about pleasing other people, Ship’s mood of mutiny is Dylan satisfying his own feelings. It heralds a turn inwards that is confirmed by the album’s closing song.

Restless Farewell is the bleakest counterpoint to the optimism which opens the album. Dylan is reminiscing about his past and bidding a dismissive farewell to past lovers, enemies, even his own thoughts and identity.

The song was a late addition to the album, one supposedly written after Dylan read a Newsweek article by journalist Andrea Svedberg that exposed aspects of his background that he had previously fudged or fabricated. You can sense his bitterness in the references to “dirt of gossip” and “dust of rumours” and the song’s general sense of having had enough of the swirl that surrounded him.

Newsweek’s exposé also inspired one of the 11 Outlined Epitaphs, which formed the extensive liner notes that Dylan wrote for The Times They Are a-Changin’. The collected poems form a sort of manifesto for Dylan the artist, but also – somewhat ironically given that Newsweek piece – reveals much about his Minnesota upbringing. The section about the media and their trivial enquiries seems to explain why Dylan will soon start approaching press conferences with a mischievous twinkle.

The Times They Are a-Changin’s various tales of injustice show that real change may not be possible. Dylan’s conclusion as expressed on Restless Farewell, is to simply decide to move on. It’s the bluesman’s choice: pull on those Spanish leather boots, say goodbye and hit the road.

Restless Farewell – one of my least favorite Bob Dylan songs – was a late replacement for one of my favorites. The beguiling Lay Down Your Weary Tune would have ended the album on a more hopeful note – “rest yourself neath the strength of strings” – while also pointing to the more symbolism-soaked songs to come.

But Dylan was no longer in the mood to portray music as a refuge or redeemer. On hearing of JFK’s assassination – just days after he’d finished recording the album – he told a friend: “Don’t even hope to change things.” He was done with protest songs.

The Times They Are a-Changin’ is more of a well-regarded than well-loved record. Many listeners find its unvarying austerity off-putting. I love its conceptual constancy. It’s a record that knows its goal and hits it with a tight set of consistently excellent songs.

And though I don’t like the final song, Restless Farewell is the right conclusion to The Times They Are a-Changin’. The title track was what people want to hear, now he does “not give a damn”. After this, we’re going to see another side of Bob Dylan.

What do you think of The Times They Are a-Changin’? Too drab to reach for regularly or a monochrome masterpiece? Let me know in the Comments below.

Leave a comment