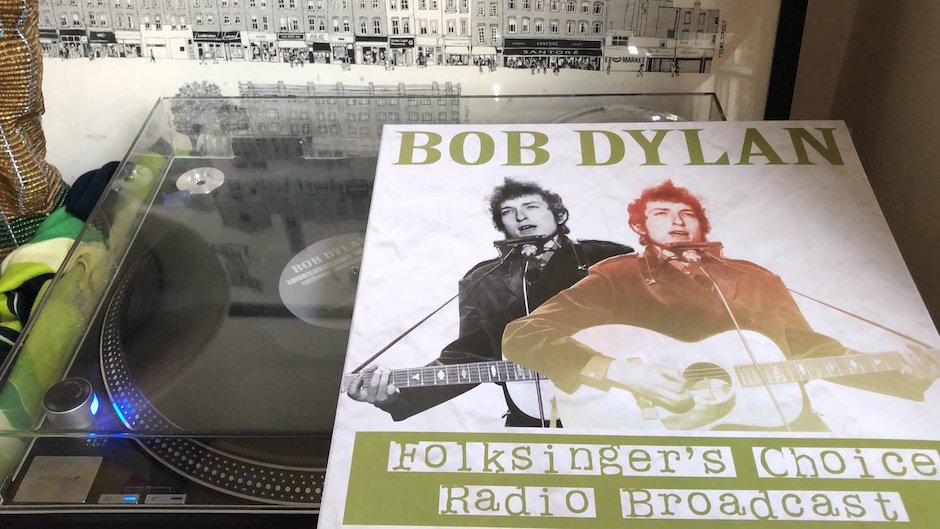

Bob Dylan’s first radio interview features sparkling conversation with host Cynthia Gooding and superb performances of original and traditional material.

“That was Bob Dylan. Just one man doing all that.”

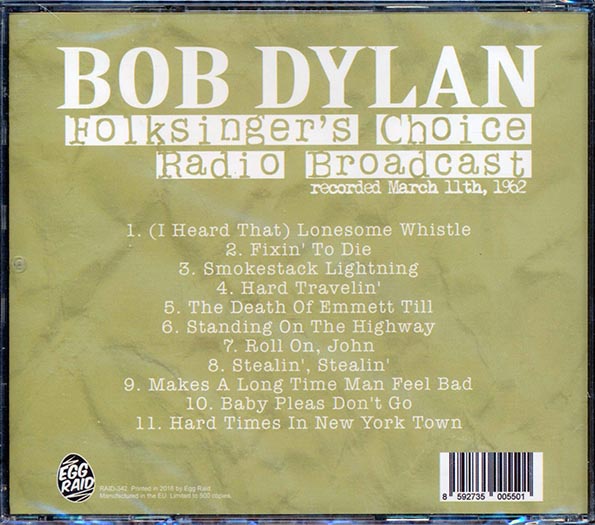

This was how Cynthia Gooding introduced the March 11th 1962 episode of Folksinger’s Choice, her regular show on WBAI 99.5FM New York.

Dylan had just played a fine version of the Hank Williams classic, (I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle. It’s a lovely, relaxed performance where he exaggerates his accent and plays with the “oh” sounds, just like Williams did.

Though it’s his first radio interview, Dylan is much more excited about playing songs than talking. It’s likely he hadn’t performed live much since a November 1961 show at Carnegie Chapter Hall, as he spent the end of that year preparing for and recording his debut album.

“You wanna hear a blues song?” he asks Gooding before launching into a track from that eponymous debut record (“that’s a novel title” she jokes). Though the radio show was recorded in January 1962 – just two months after the recording sessions at Columbia’s Studio A – Dylan appears to have already moved on from that album.

Fixin’ to Die is the only song of the 11 he plays for Gooding that features on his debut. It’s nice to hear it without the album version’s affected growl, while his guitar playing is also more expansive on this engaging take.

Gooding is a wonderful audience. After finishing Howlin’ Wolf’s Smokestack Lightning, Dylan coyly asks “you like that?” In a misty, musical voice, that’s both brusque and convivial, she tells him, “I sure do…you’re very brave to try and sing that”.

As the show title suggests, Gooding is a singer herself and had released a few albums for Elektra Records. A one-time resident of Mexico City, she recorded La Bamba before Ritchie Valens had a hit with it in 1958 and long before Dylan appropriated its chord patterns for Like a Rolling Stone.

Cynthia Gooding also recorded with Theodore Bikel, one of the co-founders of the Newport Folk Festival. A few years later, Bikel had to talk Pete Seeger down from his exasperation after seeing The Paul Butterfield Blues Band play an electric set during the 1965 edition of the festival.

Bikel wisely reminded Seeger that “these rebels, they’re us…20 years ago”. Those Butterfield radicals turned out to be Dylan’s electric heralds. After hearing Alan Lomax disparage the band’s rock’n’roll sound, Dylan recruited a few of its members to play his own raucous and loud set on the following day that scandalised the folk purists.

Dylan had become the idol of the Newport crew following the slew of topical songs he wrote in the three years between his Folksinger’s Choice and Newport 1965 appearances. Bikel encouraged the political side of Dylan, convincing his new manager Al Grossman that his charge should attend a voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi.

“Tell him it’s time to go down and experience the south”, said Bikel. Dylan took on the journey with Pete Seeger in July 1963, where he was recorded performing a stirring version of Only a Pawn in their Game.

But long before that trip, Dylan had written a Mississippi-set song, which he performed for Cynthia Gooding on Folksinger’s Choice. After a stunning version of The Death of Emmett Till, Gooding is effusive in her praise.

“It’s one of the greatest contemporary ballads I’ve ever heard – it’s tremendous.” She’s almost breathless when she says, “it makes me very proud”. When Dylan next asks “You wanna hear another one?”, Gooding replies, “I wanna hear tons”.

As much as this episode of Folksinger’s Choice is a wonderful document of Dylan’s early repertoire of songs, much of its pleasure lies in the chemistry between Gooding and her guest.

The pair have an easy patter though Gooding still slyly probes with some of her questions. When she recalls seeing him in Minnesota years earlier playing rock’n’roll, he’s quick to clarify that he was playing Muddy Waters and Johnny Cash songs.

If Dylan doesn’t want to be seen as a rocker, he’s equally keen not to be pegged too closely to the folk scene, noting that he also plays blues and country songs. Speaking about his own compositions, he states: “I don’t call them folk songs…I just call them contemporary”.

The affable folksinger Gooding seems happy to hear whatever kinds of music Bob Dylan wants to play. She is also fascinated by his harmonica holder, detailing how he puts on what she bemusedly calls “a necklace”.

“Is there a more dignified name for that?” she asks. He replies, “Uh, harmonica holder”.

Dylan was preparing to play the Woody Guthrie song Hard Travelin’, to which he adds a harmonica intro. It’s a cracking performance that builds in tempo and force and wouldn’t sound out of place on The Freewheelin’, Dylan’s second album that he will work on throughout 1962.

He straps on the harmonica again for a very lively version of the Memphis Jug Band song, Stealin’. Dylan has a lot of fun with this and you can hear Gooding laugh along throughout.

After Stealin’, Gooding asks, “You haven’t been playing the harmonica a long time, have you?” While this sounds like she’s in the Larry Adler camp when it comes to Bob’s harp skills, he doesn’t appear to take offence.

In fact, Dylan is so relaxed in Gooding’s company that he starts making stuff up. After Standing on the Highway – a self-penned song he’d later record as a demo for Leeds – she compares the lines about the ace of diamonds and spades to card reading.

Dylan uses the cue to claim that he travelled with a carnival for six years, working as a clean-up boy and on the Ferris wheel. Naturally that meant missing school but according to Dylan, “it all came out even though”.

Later he returns to the theme with a story about a woman he knew who performed as a freak and a song he wrote about her (but conveniently can’t remember). It’s remarkable stuff.

Though it sounds like he’s improvising, Dylan had previously spun versions of the carnival story to New York Times critic Robert Shelton when they spoke backstage at Gerde’s Folk City and during a show to promote his 1961 Carnegie Chapter Hall concert.

We know it’s all untrue and that Dylan had a regular middle class upbringing and schooling. But he understood that the largely middle-class folk set wanted its artists to come from less comfortable backgrounds as their own.

Back then you could get away with mythologising your past, especially with an interviewer like Gooding, who first met Dylan as a university student in Minneapolis, but is prepared to indulge his far-fetched carnie tales.These days, any such claims would be disproved in few clicks and held up as a sign of inauthenticity.

Instead of playing his carnival freak song, Dylan opts for Makes a Long Time Man Feel Bad, a work song collected by Alan Lomax around 1947 and later recorded by Ian and Sylvia. This Canadian folk duo got a record deal with help from Al Grossman, who would soon become Dylan’s manager.

They’d go on to record Dylan’s Tomorrow is a Long Time and later some of his Basement Tapes songs. They were also at Newport in 1965 and Sylvia Tyson recalls Pete Seeger crying when Dylan plugged in.

There’s a foreshadowing of such future events when Dylan plays Baby Please Don’t Go – the delta blues traditional that will be a rock’n’roll hit for Van Morrison and Them in 1964. Here Dylan uses it to showcase that he’s more than just a folksinger.

Earlier in the show, he played a gorgeous slow bluegrass song called Roll on John, which he learned from Ralph Rinzler of The Greenbriar Boys. This was the group that headlined the September 1961 show at Gerde’s that led to Shelton’s rave review of Dylan’s support act.

Gooding is enthralled by Roll on John, saying: “that’s a lonesome accompaniment too – oh my”. 50 years later, Dylan will write and record a different Roll on John for his 2012 album Tempest, as a tribute to John Lennon.

I’d love to know what Cynthia Gooding thought about Bob Dylan’s career after their magical hour together in 1962. She liked Emmett Till because it lacked “those poetic contortions that mess up so many contemporary ballads”. What did she make of Gates of Eden?

But in March 1962, none of that storied future was obviously in the cards for a man who plainly states, “I’m never gonna become rich and famous”. And he ends his Folksinger’s Choice set with that jaunty tale of struggle, Hard Times in New York.

“That’s a very nice song Bob Dylan”, exclaims Cynthia Gooding, bringing to an end a fine set from the young performer. You can listen to the entire show here:

Many of Bob Dylan’s contemporaries recall the young man’s ability to soak up songs. On Folksinger’s Choice, we are fortunate to hear an early sample of that musical range. It will inform and influence the next 60 years of Bob Dylan’s art.

An interesting post-script to Dylan’s appearance on Folksinger’s Choice is a home taped recording of him playing some songs at Gooding’s home. This took place on Feb 16th 1962, between the date of the radio show recording in January and its broadcast in March.

Dylan was there with his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, Gooding and her two daughters, along with Mel and Lilian Bailey, prominent figures in the folk scene. It was Lilian who convinced the owner of Gerde’s to give Dylan his life-changing shot at performing there.

The Baileys had recorded some of Dylan earliest performances so it’s seems likely that they made this tape, though it may have been the host, Gooding. It’s a fascinating record of friends hanging out while Dylan plays some songs with lots chat in between.

The tape starts with a wobble as Dylan’s sped up voice sings the opening line of The Ballad of Donald White. But it quickly corrects to the right speed for this Dylan original that relates the lengthy tale of a man about to hang for murder.

Somewhat naïve and melodramatic, you can see why he dropped Donal White from his repertoire, aside from one more home recording in September 1962. But for an early attempt, it shows that Dylan already has a decent grasp of how to pace and structure a narrative song and his performance is poised and passionate.

The music is based on the Scottish traditional Come All Ye Tramps and Hawkers, which makes Donald White a modest precursor to Dylan’s much more complex I Pity the Poor Immigrant from 1967’s John Wesley Harding.

After a discussion about the guitar he’s playing, Dylan performed Wichita (Going to Louisiana), which is generally credited to Robert Johnson though a song of that title doesn’t seem to feature in the bluesman’s list of recordings.

Dylan absolutely nails this one, hitting some high notes and playing his guitar with pace and intensity. “Oh wow,” exclaims Gooding as he finishes and you can hear that the room enjoyed the performance. Dylan will try out Wichita during one of the sessions for his second album, The Freewheelin’. Though it didn’t make the final cut, the rare outtake is a fun listen.

At Gooding’s request, Dylan plays Acne – a comedy song written by Eric Von Schmidt – and gets the whole room laughing with his teen pop song parody voices. Lilian Bailey suggests that Columbia would make millions if they released it.

Perhaps wanting to be taken more seriously, Dylan launches into Rocks and Gravel, another one that he’ll record for The Freewheelin’ but leave on the cutting room floor. His voice sounds great here as he elongates the words then repeats certain lines with a bluesy spoken growl.

Later in the year, Dylan will play Rocks and Gravel at The Gaslight, where his guitar playing has evolved to be a lot more intricate than the simpler picking on the version at Gooding’s home. Someone in the room tried introducing a tambourine during Rocks and Gravel but struggled to find the rhythm.

The unnecessary percussion continues on Long Time Man Feel Bad, which Dylan had played for Gooding on her radio show. Unfortunately this promising take is cut short as the Cynthia Gooding Tape ends halfway through Dylan’s hushed performance.

Apparently he also played the Woody Guthrie song, Ranger’s Command but I can’t find it. There is a recording of that song that is often mislabelled as being from this Gooding session. But it sounds nothing like the rest of the Gooding tape and is likely from a 1961 show at Gerde’s.

Cynthia Gooding played a significant role in encouraging, recording and promoting Bob Dylan during the early part of his career. Both the Folksinger’s Choice broadcast and the home recording showcase Bob Dylan’s development as a performer and songwriter in the months following the recording of his debut album, while highlighting the warmth and support he received from people like Gooding.

What do you think of Bob Dylan’s Folksinger’s Choice radio appearance and the the Cynthia Gooding home tape? Let me know in the Comments below.

Leave a comment