Early bootlegged live performances featuring Dylan originals and folk classics.

When I revisited Bob Dylan’s 1962 self-titled debut album, I found it to be a surprisingly un-Bob Dylan record. For a better sense of who the singer really was, it’s worth hearing what he was playing live around Greenwich Village’s coffee houses during the early 60s.

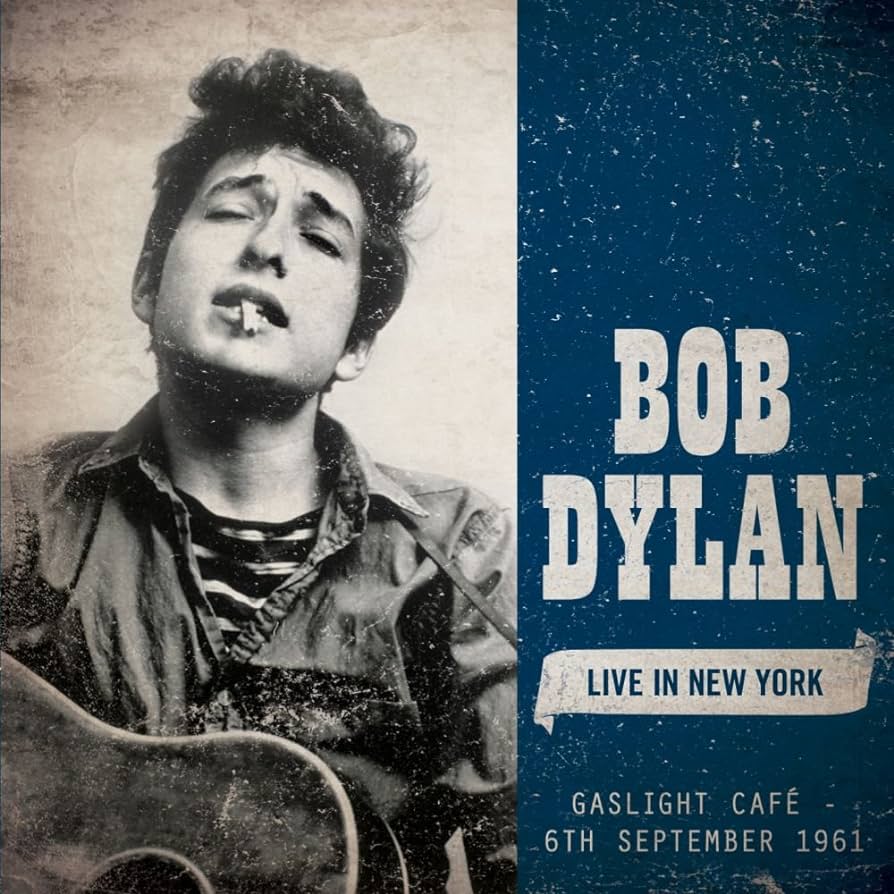

The Gaslight Tapes is the name given to a 1962 recording of a pair of live Dylan sets at New York’s Gaslight Café. They’re often considered one of rock music’s first bootlegs. But before I revisit them, let’s go back even further to September 1961 – two months before Dylan recorded that muddled debut album – and hear a short six-song set at the same venue.

The lower Manhattan neighbourhood of Greenwich Village had been a home for the arts since the mid-19th century construction of the Tenth Street Studio Building, a dedicated artistic facility that was designed by Richard Morris Hunt, who also created the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal and the Great Hall of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1938, the first racially-integrated nightclub in America – Café Society – opened in the Village and played host to the stars of the country’s burgeoning jazz music scene. By the 1950s, Greenwich Village had become a bohemian centre attracting poets and writers like James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Dylan Thomas, who died there in November 1953, aged just 39.

The American folk music revival became part of the Village’s bohemian scene, due in part to its socialist associations forcing it underground at the height of the Red Scare / McCarthy-ite culture war during the 1950s.

In 1957, folk enthusiast Izzy Young opened The Folklore Centre on MacDougall Street, helping establish Greenwich Village as the centre of the folk world. Young later had a hand in turning a West Village restaurant into a music venue that eventually became Gerdes Folk City in 1960.

A year later, a coffee shop called The Bitter End on Bleeker Street also became a music venue that was soon famous for its Tuesday night folk music hootenannies. The cavern-like Café Wha?, which opened in 1959, was the venue that Bob Dylan played on his day he first arrived in New York in January 1961.

The Gaslight Café had opened in 1958 and originally hosted beat poets like Allen Ginsberg, before expanding its repertoire to include comedians such as Lenny Bruce, and musicians, including one-man band Jesse Fuller, the incomparable Odetta, jazz bassist Charlie Mingus, future Dylan collaborator Happy Traum, the Rev. Gary Davis (about who more later) and The Greenbriar Boys.

The latter were a bluegrass group who met in Washington Square Park and featured as guest players on Joan Baez’s second studio album. The Greenbriar Boys was the headliners of a show at Gerdes in late September 1961 that Robert Shelton reviewed for the New York Times.However, the music critic decided to focus his attention and praise on the evening’s support act, Bob Dylan – most likely after weeks of pestering for a write-up from Dylan himself.

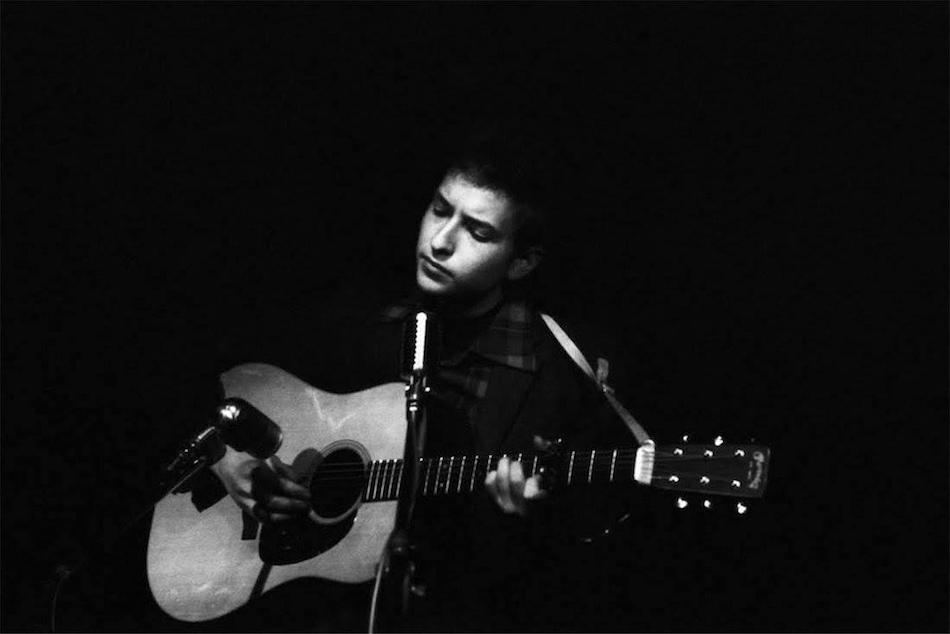

The first Gaslight recording happened on September 6th, weeks before that pivotal Gerdes’ show and before Dylan had first met John Hammond, the Columbia executive who signed him to the label. The tape is an opportunity to hear Dylan just before his career starts to take off, as well as one of the earliest recordings of him playing his own compositions.

You can listen to Dylan’s entire performance here:

The set starts with Man on the Street, a restrained piece of social observation that lays the ground for the many protest songs to come. A couple of months later, Dylan would record this original composition during the sessions for his debut album, though it would not make the final tracklist.

The same is true for the next song in this Gaslight set, He Was a Friend of Mine. This Rick Von Schmidt song is a real gem and Dylan’s performance at The Gaslight is possessed by an extraordinary stillness. You can feel this young man capturing an audience with a wisdom and grief that would surely have seemed beyond his 20 years. Someone lets out a “yeah” as soon as Dylan finishes the song and the sense of surprise and wonderment wrapped up in that exclamation aptly sums up the experience.

Dylan has claimed that Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Disaster Blues was the first song he ever wrote. It was inspired by a news story that Noel Stokey – MC at the Gaslight and later “Paul” of Peter, Paul and Mary – brought to his attention. As we’ll come to see more and more with Dylan, the actual truth of a story rarely gets in the way of a good song.

The Hudson Belle was a large steamboat that ran regular day cruises on the Hudson River to resorts upstate in Bear Mountain. One Father’s Day, counterfeiters sold fake tickets meaning that the cruise was over-subscribed. The excess number of day trippers led to a delayed departure and fights that resulted in some people – maybe a dozen – being hospitalized.

Dylan’s version is much more dramatic and comical. In his introduction to the song, he says that the “boat was sinking down the water there was so many people” and suggests that policeman and firemen were pulling people out of the river.

In the song itself, his narrator is a naïve victim who sees six thousand other potential passengers and thinks “the more the merrier”. Amid the ensuing mayhem, he loses track of his kids and wife, even loses consciousness and his sight but somehow manages to retain his picnic basket.

Dylan the songwriter is not so guileless. He cleverly shapes the farce into something more meaningful into a pointed final verse designed to appeal to the anti-capitalist instincts of the hardcore folk crowd, as he sings:

“Well, it don’t seem to me quite so funny

What some people are gonna do for money.

There’s a brand new gimmick every day

Just to take somebody’s money away”

Dylan will record Bear Mountain Massacre Blues during the Freewheelin’ sessions but the song never seemed like a serious contender for inclusion on the final album. Besides, it works best live when you can hear the audience laughing along, especially here when a man repeats Dylan’s sardonic “yippee”.

Next comes one of the two originals that Dylan did include on his debut album. It’s interesting to hear how Song to Woody developed from the slow, almost plodding version he plays at the Gaslight to the more affirming, upbeat recording he cut in November.

Song to Woody’s lyrics reference Guthrie’s own Pasture of Plenty. Then Dylan proceeds to play Pretty Polly, whose music was the basis for Pastures of Plenty. The centuries-old murder ballad will soon be the musical template for The Ballad of Hollis Brown, which Dylan will write within a year.

At the Gaslight, Dylan gives a mesmerizing performance of Pretty Polly with intricate guitar playing and intense vocals, all while tapping out the rhythm with his foot. It’s likely that the recording missed the first part of the song unless Dylan decided to skip its usual opening verses of courtship and went straight for the menace and murder.

Finally, Dylan is joined by Dave Van Ronk (“he’s an ex-blues singer”) for a fun version of the Woody Guthrie song Car Car that sees the pair honk and brrrrp in harmony like old revving engines.

Overall, the 1961 Gaslight performance is much more indicative of the recording artist that Dylan will soon become than the album he’ll commit to wax just two months later. It’s definitely worth a listen.

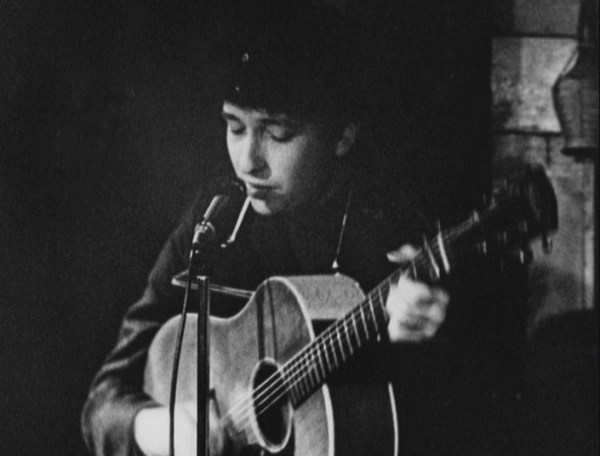

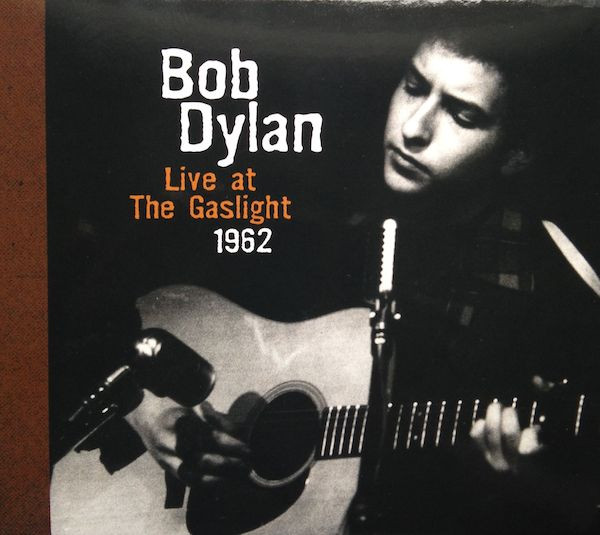

Just over a year later, with that self-titled debut album barely resonating beyond the Greenwich Village folk circuit and a new, ambitious manager, Albert Grossman, guiding his career, Dylan returned to the Gaslight Café.

The 1962 Gaslight Tapes were recorded over two sets on October 15th by audio engineer Richard Alderson, who connected his reel-to-reel tape recorder to the venue’s PA system. Alderson had previously captured a Nina Simone live set at The Village Gate – just around the corner from The Gaslight – that was officially released on the Colpix label in early 1962. And the sound man would again record Dylan four years later on the infamous electric tour.

The Gaslight recordings demonstrate how Dylan’s performances and songwriting had progressed in the year since his last appearance at the venue. It’s also — possibly uniquely — a harmonica-free solo performance.

You can hear the 1962 performance on the YouTube video below (though it’s missing some songs and the running order differs from what the detectives over at Bob’s Boots concluded it should be).

Dylan had spent much of 1962 in the studio, looking to put the disappointment of his debut record behind him. Though he was now writing a lot of songs, the first of the 1962 Gaslight sets is mostly folk standards, like the opener Motherless Children.

Motherless Children was written by Blind Willie Johnson, who as a child was blinded by his stepmother. On Johnson’s recording of the song, he forces every ragged edge of that remembered agony out through the grinder of scratchy singing voice.

Dylan’s Gaslight take on the song is fine and we’re thankfully spared the grizzled bluesman affectation that weakened some of the songs on his debut album. As covers go, I’m more inclined to point you towards this dynamic version by the Rev Gary Davis, that must have inspired Ray Charles’ I’ve Got a Woman.

Next comes Dylan’s ok take on the lovely Handsome Molly, an Irish courting ballad that crossed the Atlantic to become a bluegrass standard. It was popularized by The Stanley Brothers in the 1950s, who also did the same for the 1913 traditional Man of Constant Sorrow, which Dylan recorded for his debut album.

Handsome Molly was very much in the air around the time of Dylan’s Gaslight performance. The Stanley Brothers had released a new version in 1961, while future Dylan collaborator Earl Scruggs and his partner Flatt, recorded it a year later. My favourite take is by another blind singer and guitarist, Doc Watson who does a cracking banjo and fiddle version.

The set’s first original is John Brown, which draws from other folk songs like the Irish ballad Mrs McGrath, recorded by Dylan’s friend Tommy Mackem. Growing up in Ireland, Mackem and his bandmates The Clancy brothers were part of the furniture when it came to television, radio and my parent’s record collection.

I was astonished when Liam Clancy showed up in Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home documentary telling stories about a young Bob Dylan. It turned out these Aran sweater wearing old fogeys were a big part of that early 60s folk scene in Greenwich Village and were people that Dylan looked up to.

John Brown is a compelling story of a proud mother who sends her son to war but must confront the reality of combat when he returns disfigured and angry. Dylan pulls no punches with his grizzly detailing of the son’s injuries. But this long song loses its way, as the title character strays into more obvious observations about the enemy being just another young man like him.

Dylan later cut John Brown as a demo for Witmark, which you can hear on the Bootleg Series Vol. 9, and recorded it under the pseudonym Blind Boy Grunt for the 1963 topical song collection, Broadside Ballads, Vol. 1. He also made an unexpected revisit to John Brown 30 years later during his MTV Unplugged set.

A full two years before its official release on his third album The Times They Are A-Changin’, Dylan performed The Ballad of Hollis Brown at The Gaslight Café. The main guitar part is strummed here – it’ll evolve to be a largely picked riff – and we get an additional verse about bed bugs and gangrene.

Even at this early stage in its development, Hollis Brown packs a punch and must have impressed those in the Gaslight audience who recognized it as a Dylan original that evolved well beyond its obvious Pretty Polly origins.

Dylan’s blaring harmonica often obscures his guitar playing. At this harp-free Gaslight show, we get to appreciate some fine picking on Cuckoo is a Pretty Bird, a traditional English song that may date back to the 18th century.

Appalachian banjo player Clarence Ashley recorded a version of Cuckoo in 1929 that later appeared on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, the 1952 collection that had a huge impact on the folk revival and on Bob Dylan.

There’s more standout guitar playing on a great rendition of Robert Johnson’s Kindhearted Woman Blues. Columbia Records had released a collection of the mythical bluesman’s rare recordings in 1961 and John Hammond had given Dylan a copy after signing him to his label. Given how well he performs Kindhearted Woman Blues at The Gaslight, it’s surprising that Dylan never returned to this song again during his long live career.

It’s back to simple strumming for an effective take on Ain’t No More Cane, a prison work song that is often, if inconclusively, attributed to Lead Belly, the singer and guitarist who folklorists John and Alan Lomax first recorded in Louisiana’s Angola Penitentiary. Dylan will return to Ain’t No More Cane later in the decade when he’s down in the basement with The Band.

Cocaine was originally written by bluesman and white powder aficionado Luke Jordan but this Gaslight arrangement is based on a version by Rev. Gary Davis, another blind bluesman, who Dylan would later call “a wizard of modern music”. The deliberate disintegration towards the end of his performance of Cocaine is a rare moment of fun from Dylan in this otherwise serious Gaslight set.

Blind Lemon Jefferson’s See That My Grave Is Kept Clean is the only song from either of the 1962 Gaslight performances that featured on Dylan’s debut album. Here he smooths out the affected vocal roughness from the recorded version and sounds much more like himself.

The closing song of this first set is West Texas, which is credited as a traditional but there’s little evidence of anyone performing it before Dylan. “I’m going out to West Texas, behind the Louisiana line.”, he sings, even though the state line in question borders East Texas.

This iffy geography could indicate that it’s a Dylan’s original. Despite his myth-building claims to being a country-wide wanderer, he probably hadn’t been anywhere near either of those states by this point in his life.

West Texas is a long song, well over five minutes with an intense rhythm and lots of familiar blues and Dylan tropes, like wells running dry and fortune-telling women. The Gaslight recording sounds distant, like you are listening in from outside the room as Bob Dylan rehearses the kind of song he’ll become extremely good at writing very soon.

The second half of Bob Dylan’s 1962 Gaslight Café set starts with A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, the legendary song that he supposedly wrote about the Cuban Missile Crisis, though the presence of Russian missiles on the Caribbean Island wasn’t made public until a week after this show.

In fact, Dylan had given Hard Rain its live debut the previous month at the Carnegie Hall Hootenanny. Those present recalled how he produced multiple loose sheets of paper containing the lyrics then unleashed a song like no other on an unsuspecting audience.

But Dylan had also been recorded playing Hard Rain two days before the Carnegie Hootenanny at the home of Eve and Mac McKenzie, where the singer often crashed during his early couch-surfing days in Greenwich Village.

Back at the Gaslight, we can hear how the lyrics have already evolved since its first outings – “my blue-eye boy” becomes “…son” – and his performance is increasingly confident. Plus, someone in the crowd knows the song well enough to sing along.

It’s remarkable to hear Dylan capture the apocalyptic mood of the country’s impending crisis, just days before it became a reality for the majority of Americans. Hard Rain is an early example of his uncanny ability to tap into the prevailing winds and anticipate which direction to turn.

Next comes the first live recording of the superb Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right. It’s possibly the first song Dylan wrote about his personal relationships, in this case his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, who had moved to Italy to study. She left behind a broken-hearted Dylan, though he expresses this through affected nonchalance about a relationship’s end.

Black Cross is a spoken-word piece that was originally a poem by Joseph S. Newman (uncle of the famous actor and salad dressing impresario, Paul). The simple guitar arrangement is based on a version of the song by 1950’s character comedian Lord Buckley, who Dylan would later call a “hipster bebop preacher” in Chronicles.

Black Cross is the story of a black man – Hezekiah Jones – who is hung by a preacher for preferring books to religion. But this tragic tale is told with a sardonic edge summed up by the closing lines where the “white folks around” suggest Hezekiah had it coming for his lack of faith. Dylan’s laconic delivery is perfect though unfortunately he mixes up some key details, which confuses the story a little.

Continuing the theme of the oppression of America’s black people, Dylan then plays No More Auction Block, a traditional song sung from the perspective of a freed slave. The singer, actor, pro-footballer and all-round Renaissance man Paul Robeson sang the song in his extraordinary bass-baritone on a 1950s recording, while Odetta released a haunting version on her 1960 live album, Odetta at Carnegie Hall.

Dylan’s plays his own arrangement of No More Auction Block in this powerful Gaslight performance and we’ll soon hear its echoes in his breakout composition, Blowin’ in the Wind.

While Rocks and Gravel is a Dylan original, it’s essentially a fusion of multiple blues standards. One of these is Rocks and Gravel Make a Solid Road by bluesman Mance Lipscombe, who will appear on the same bill as Dylan at the 1963 Monterey Folk Festival. Dylan also pilfered lyrics for Rocks and Gravel from the superb Alabama Woman Blues by the high-regarded singer Leroy Carr, who died tragically young in 1935.

Dylan had recorded Rocks and Gravel during one of the first Freewheelin’ album sessions back in April 1962, but the song was cut from the final record just weeks before its release a year later. It’s great to hear this exceptional performance at the Gaslight which Dylan builds to a dramatic climax. And he would reuse Carr’s lyrics a few years later on Highway 61 Revisited’s wonderful third track, It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.

Samuel Pepys mentions the song Barbara Allen in a 1665 diary entry but this oldest of ballads continued to resonate 300 years later. Suze Rotolo recalled how the folk crowd saw her as the “hard-hearted” title character with Dylan as the tragic William, who appears to die from unrequited love.

The Gaslight version is a wonderful take on a lovely, lengthy song that Dylan continued to play live throughout his career. He also said that without Barbara Allen, there would be no Girl From the North Country.

The Gaslight set closes with Moonshine Blues, a song Dylan supposedly learned from Liam Clancy though this soft, hushed lament is nothing like the rowdy, drinking song as performed by the Clancys.

Dylan will record the song as Moonshiner a year later during The Times They Are A-Changin’ album session. It’s another song that won’t make the final tracklist of a Dylan album but decades later the outtake will be one of the highlights of the first Bootleg Series.

The 1962 Gaslight Tapes are essential listening for any Dylan fan, with early recordings of some of his best songs, the first overt references to racial injustice and some beautiful traditional pieces.

After decades of only being heard by those with a bootleg copy, The Gaslight Tapes got an official release of sorts in 2005, when 10 songs were collected for a Starbucks exclusive CD. Of course, this outraged some fans, who accused Dylan of selling out to a corporation (hadn’t they seen the Victoria’s Secret commercial?).

It also upset record retailer HMV, whose Canadian arm removed all Dylan releases from their shelves in protest at a café chain infringing on their business. Talk about focusing on the wrong threat when the iPod and Napster had already opened the digital Pandora’s box.

Together the 1961 and 1962 Gaslight Tapes provide essential insights into where Bob Dylan was going ahead of the release of his breakout album, The Freewheelin’. But even aside from the historical perspective, it’s just a treat to hear these fine performances of some great songs — especially if you’re not a harmonica fan.

What do you think of the 1961 and 1962 Gaslight Tapes? Let me know in the Comments below.

Leave a comment